[3.5 mins reading time]

The waiter says, “This is the first ever. The first summer I can’t ski the Marmolada.”

The Queen of the Dolomites, the glacier’s on the north face of the mountain. Losing ten centimetres of ice every day. The oracle says: prospects gloomy.

A hundred years ago, an avalanche on the Marmolada killed two hundred and seventy soldiers. Their remains, their mashed belongings, both are being released by the glacier.

The boatmen of the great River Po don’t need to say a thing. The Po is in the top three Mediterranean rivers by water discharge, along with the Rhone and Nile. Normally. Or at least, till recently.

The watermen stand on the bank, on the stranded bridges. They see sandbank and gravel. For one hundred kilometres the river is dry. This artery of water trade. Silenced.

The iceman called Ötzi is lying in a glass coffin. All sinew and leather, misted with moisture, as cold as he’s been for the past five thousand years.

He was up in a glacier. Until it started melting. He’s older than the desert pyramids, older than stone henges of the north. Now he’s lying in a museum, in a medieval mountain town.

It’s early summer, the season of honey and rustling birch. Birdsong in the forest. The band of men are walking south, up and over and aiming for the sea. They intend to follow dashing rivers fed by snow and ice, down to the glittering azure sea. They’re not going for food or supplies, for this is a walk of hundreds of leagues and dizzying passes. They’re going for story. What can be learned from the people down at the shores. What they can share too.

The leader of the band is the shaman.

He’s about forty-five years old, the age of an elder. Ötzi’s wearing clothes of leather and braided grass, stitched with sinews. A bearskin hat with chinstrap, his shoes are part grass, part deer hide, the fur side inwards. His coat is made from strips of goat and sheep hide.

He carries fire. Two birch bark containers, charcoal embers wrapped in maples leaves, easily fanned to flames in seconds. He’s dark-skinned, has long hair and brown eyes. He’s got a map on his skin, sixty tattoos at acupuncture points. Up on arm and back, down on shins. A chart of health, how to keep healthy too.

In his calfskin belt-pouch, antibiotic birch fungus, dried plants, twisted hide.

What else is there about this shaman older than Gilgamesh, the early writer of stories. He’s had Lyme disease, is carrying whipworm in his guts. His teeth are worn, there’s a diastema gap between incisors. Falls or fights have broken ribs and nose, sometime ago as an adult. He got a deep wound in his right hand, a few days ago. He’s been eating venison, grain, leafy plants.

The band is armed, for hunting animals. Long bow of yew and fletched arrows of viburnum and dog wood, a copper axe. This is their invention to share. How to smelt copper and other metals. Ötzi’s also carrying a fine flint dagger and a retourcheur to sharpen flint, made from birch bark and tipped with antler.

They’ve been climbing up through pine. The air is filled with resin, the trees themselves fixed by clinging roots to rock. Pine needles cover the floor, soften their steps.

The views are spectacular. Alpine meadows and pale limestone mountains, sharp peaks. Hard blue skies and bubbling clouds. Great slabs of rock, pillars by the path, pointing upwards to the gods. By mid-afternoons, grumbling thunder and warm rain.

They’re walking in early morning mist over the pass when Ötzi stumbles. He falls into rocks, spins out onto the glacier itself, down into a crevasse. He has an arrow deep in his left shoulder. It’s punctured a vital artery.

The band hears the zip of arrows. They scuttle and scatter, the mission over.

His attackers are frustrated. They don’t find Ötzi. Or his treasures.

One last search by his band that night, creeping back. But can’t locate him.

It’s failure for the attackers, a futile death at their high cold border.

He’s going to be absorbed by this glacier, for fully five thousand winters more.

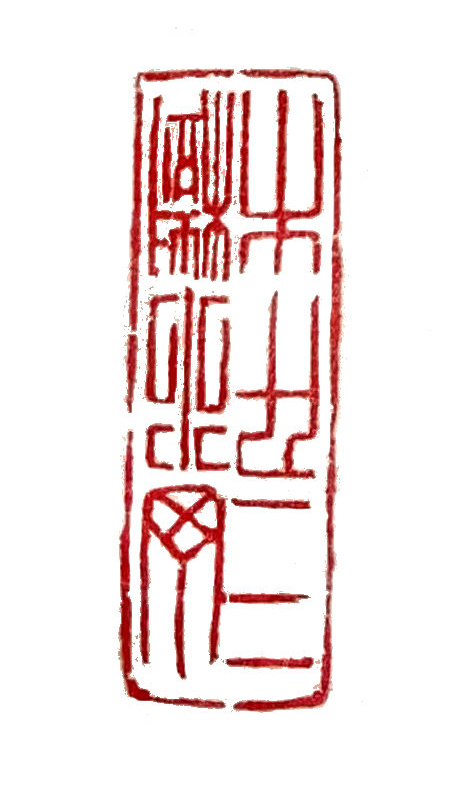

Jules Pretty

Jules Pretty