[4.5 mins reading time]

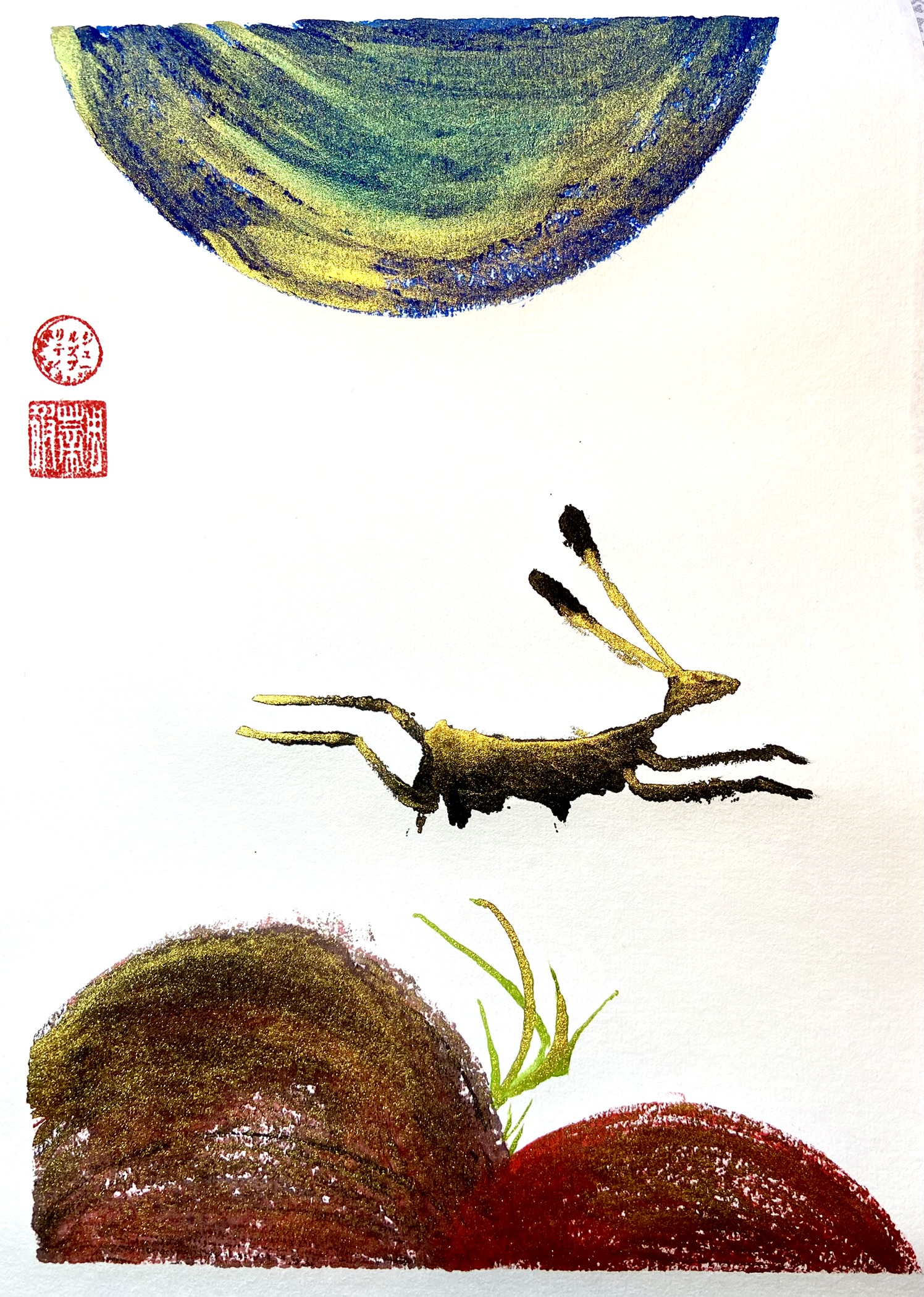

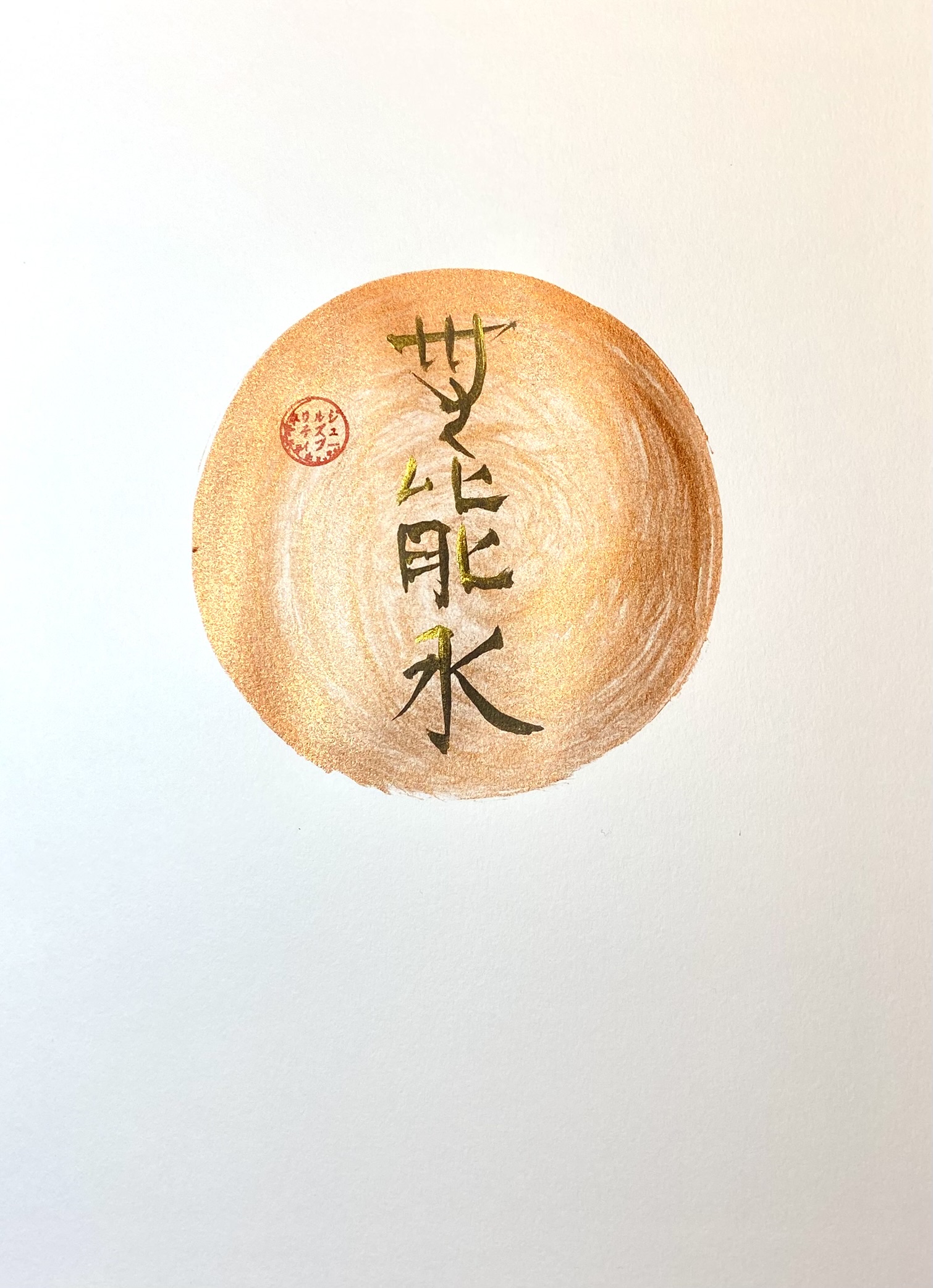

Mu Nou Ei (Not Knowing is Most Infinite)

Sometimes not knowing is good.

You could just, well, be content. Then let a small thing open the way to a greater mystery.

Hare is captain of a company of tearaways. When he is young.

This is how he learns that vastness is his home.

This is why the hare comes to love the open fields, even has youngsters in the open air, eyes wide, ready to run. Born in the chime hours, so bound to have second sight.

They can run, after all, faster than the wind.

The Great Hare is the transformer at the edge of things.

Hare springs up, comes out of fire-ash faster than a phoenix, lives under the silver moon. Where do they go, people ask? Those graceful leapers? So many in the fields, you look again and there’s no-one there.

Even as adults, they only eat at night. Walk to the middle of a field, and you may find them sitting in a circle, the hares’ parliament.

Hare still today can cross to the land of the dead and talk to all those shades and shadows.

This is the thing about tricksters.

They often make a mess, get it all wrong. But in doing so, they provide some guidance, some insight. What we should do, and what not. They are rehearsal for the real thing.

Every culture has them. Butterfly, Coyote, Fox, Green Turtle, Green Willow, Raven, Spider, Wolverine. And Hare.

The Great Hare is the goddess Eostre’s favourite spirit. There are Tinners’ Rabbits, three sharing three ears, the jade rabbit in the Chinese moon, Br’er Rabbit, Jack Rabbit. All dressed in fine fur, long ears. Fast.

Hares, not rabbits, in other words.

In eastern England, the Hare is the trickster with eighty names. Hare is Owd Sally, Owd Sarah, the one haring-away, the hare-brained and the leaper, the one who springs to a truth, the frisky one, the lurker in the ditch, the skulker and the springer. The hare’s mind is creative and active. The hare is the looker to the side, the one who doesn’t go home straight.

There is one Great Hare called Glooskap.

Now it comes to pass, Glooskap has defeated all the giants and sorcerers, every magician and all manner of evil spirits. He’s tapped on walls, stared into wells. He thinks his work is done, so time for a snack.

It’s winter. A fine afternoon, so no need yet for candles.

A certain woman is leaning on a garden gate. She says, “Not so fast Mister, for there remains One who will remain unconquered for all time.”

“And who is this One?”, inquires the Hare.

“It is the mighty Wasis, and there she sits.”

Now Wasis is the Baby, and she sits on the lawn sucking a piece of maple sugar, greatly contented, troubling no one. Hare leaps over, turns to Baby with a bewitching smile. He tells her to come to him, his voice sweet like the summer bird.

Baby smiles, and does not budge.

Glooskap speaks loudly, his many voices ringing. And Baby bursts out crying, but does not move for all that.

He uses his most awful spells, and sings songs which could raise the dead and scare devils.

And still she sits and looks on admiringly. She seems to find it interesting. But all the same never moves an inch.

Glooskap gives up.

And Wasis on the floor in the sunshine goes goo, goo! And cooes again. And to this day, you can see all babies are well-contented and going goo, goo!

For of all the beings that have ever been since the beginning, Baby is alone the only invincible one.

Baby now picks up a coloured brick. Holds it. Hands it over to Hare.

Hare is thinking, how interesting. This baby is being kind.

She is saying, “we” rather than “me”.

And the Great Hare, he learns from Baby to have a smooth mind. To try to sway aside when arrows come in fast. To be kind.

A child asks forty thousand questions before the age of five. Always why. Never, where’s the evidence? Never, show me the data.

Hare goes off to talk to his friends.

He’s the one with honey eyes, the trickster often with bees in his fur. The one who makes things slide sideways, quite fast.

Fantastic isn’t it? An old god of all the places and their shadows.

An animal whose song grows stronger.

One who now knows what hope is.

Commentary on Mu Nou Ei: Not Knowing is Most Infinite

In the legendary 1930 classic, Zen and Japanese Culture, Daisetz Suzuki said, go back to your infancy, and observe. The great earth may crack, and the child remains unconcerned. A burglar may break into the home, and she smiles at him. “Would a baby be overjoyed if the empire was given to her, or she was decorated with a medal,” asked Suzuki. What concerns the child is the absolute present.

The infant as yet knows no fear, no insecurity, does not need to be something nor live up to some expectation. There is anxiety about food and comfort, but not much more. Quite soon, though, this begins to change.

Christina Feldman and Willem Kuyken asked in their book, Mindfulness, what does it mean to be happy and to live the good life? They observed that mental ill-health was now a one-billion-person worldwide problem, and that through a combination of ancient wisdom and modern science we might just, quite literally, “Come to our senses.”

The Great Hare with honey-coloured eyes, jewels gleaming, the trickster often with bees flying round their fur. The one who makes things slide sideways, quite fast.

Hare says: “I prefer coles and worts, any kind of brassica and cabbage. Do you have some? It’s always good to bring a gift.”

Said Morikei Ueshiba, the founder of Aikido:

“Always keep your mind as bright and clear,

As the vast sky, the great ocean,

And the highest peak, empty of all thoughts.”

Jules Pretty

Jules Pretty