[3 mins reading time]

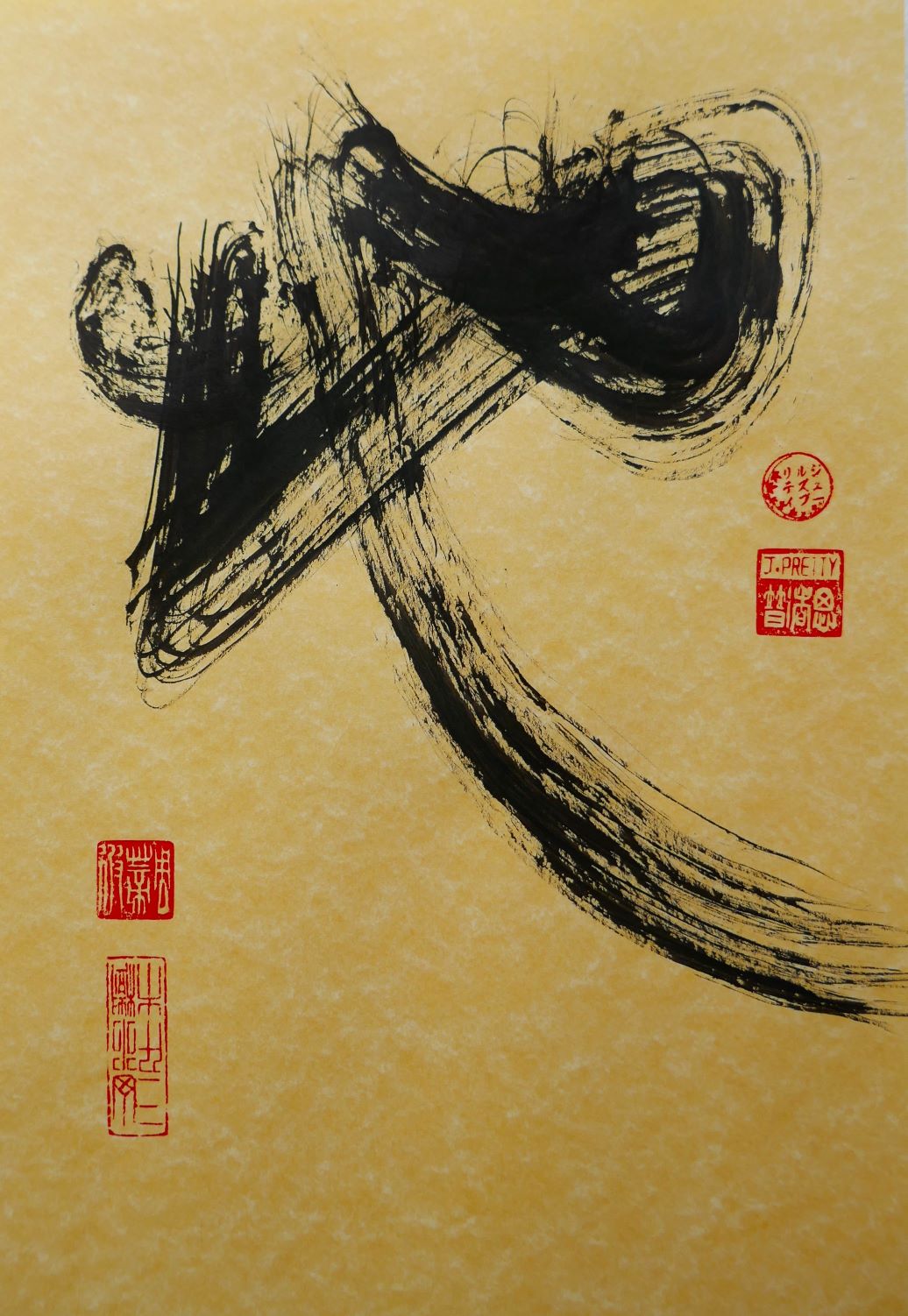

Chi Ka: Earth Transformed

The people at the back hear the sound of drums first.

They part, stand aside.

A tall man with silken skin walks up.

Well now, this is Eshu. His voice is deep and it rings and rolls. He wears a necklace of cowrie shells.

He has crossed seven rivers and three motorways, walked along dark forest paths, over slopes scorched since the long rains.

He carries a goatskin bag with magic things inside, a drinking horn, a machete and snuff. His left eyelid twitches when he sees something from the future.

He has skirted silent villages where women send their voices over compound walls, where their children play under the moon at night.

He stands with feet apart, crosses his arms. Looks around.

“Listen,” he says to the crowd.

“Here is a story for this very dusk, to make the coming night as fresh as flowers.”

Eshu is always strolling along, in the middle of the path. This is the story.

One day he is wearing his four-coloured hat, these are the colours of the world.

He comes to some fine farmland where he’s heard there were disagreements, time and again. Arguments flaring up, how we should see the world.

Some farmers want to let wild trees grow green, provide shelter and give crops water from their roots.

Others think they ought to stay with the modern ways of monoculture.

He sees two farmers who are best friends. He walks on the dusty path that winds between their farms, partly in the shade of mimosa and other healthy shrubs. It is the season for hoeing rows of yam.

It’s been a hot and uncomfortable afternoon. The two farmers talk on the way home.

They are thirsty and tired.

“Who was that strange fellow with the white hat?”

“Hmm. That stranger? Wearing a red hat.”

White-red, red-white, they soon become cross with each other, as they walk.

By the time they come to the village square, they are shouting and shaking heads.

A crowd gathers at the place right where wrestlers and boxers used to meet. It’s been market day, and there are still stalls and visitors from far.

By now the two men are bunching hands, forming fists. One draws a knife. Now the crowd of men and boys and women carrying their children are shouting too. Their wives and the headman are at a loss.

The children are crying.

“Yes in those days,” says Esu. “There seemed more crying.”

“This is the problem. No one has easy answers.”

The crowd is silent as he speaks. He returns to the story, speaking to the two farmers.

“There never is one sole truthful view of the world. Your vows of fruitful friendship should have been strong enough. But look, now you want to fight.”

“Stop it right now. Look at my hat.”

The market people turn, nod to one another. The two farmers were looking down at their feet.

Now Eshu takes some cowries from his necklace. He passes them out to the women and their children.

It is later said, by many, Eshu did help us heal ourselves. So we owe him sacrifice.

Now the people think: they should be looking with all their eyes.

“Both of them were right, heh?”, says Eshu.

Jules Pretty

Jules Pretty