[6 mins reading time]

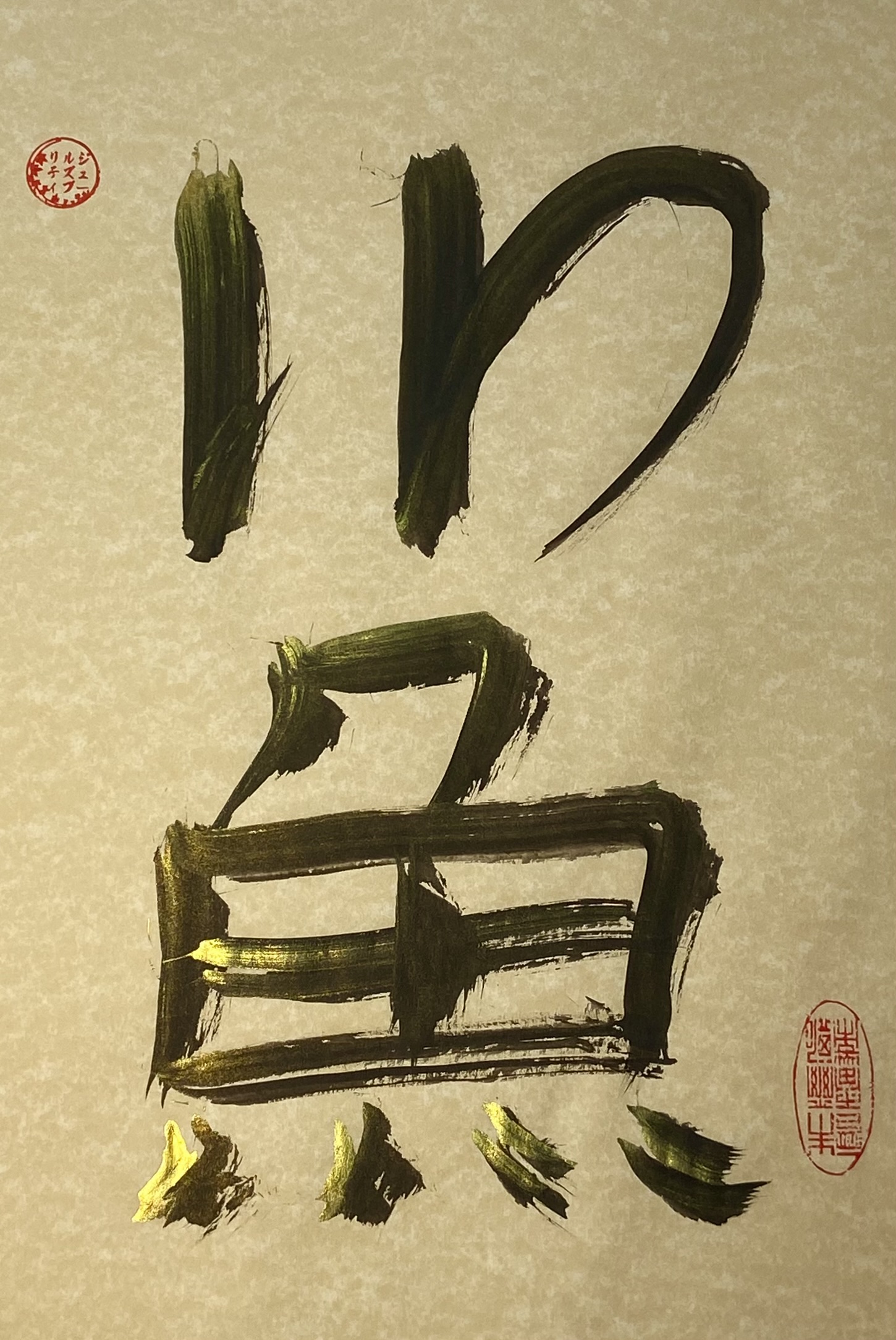

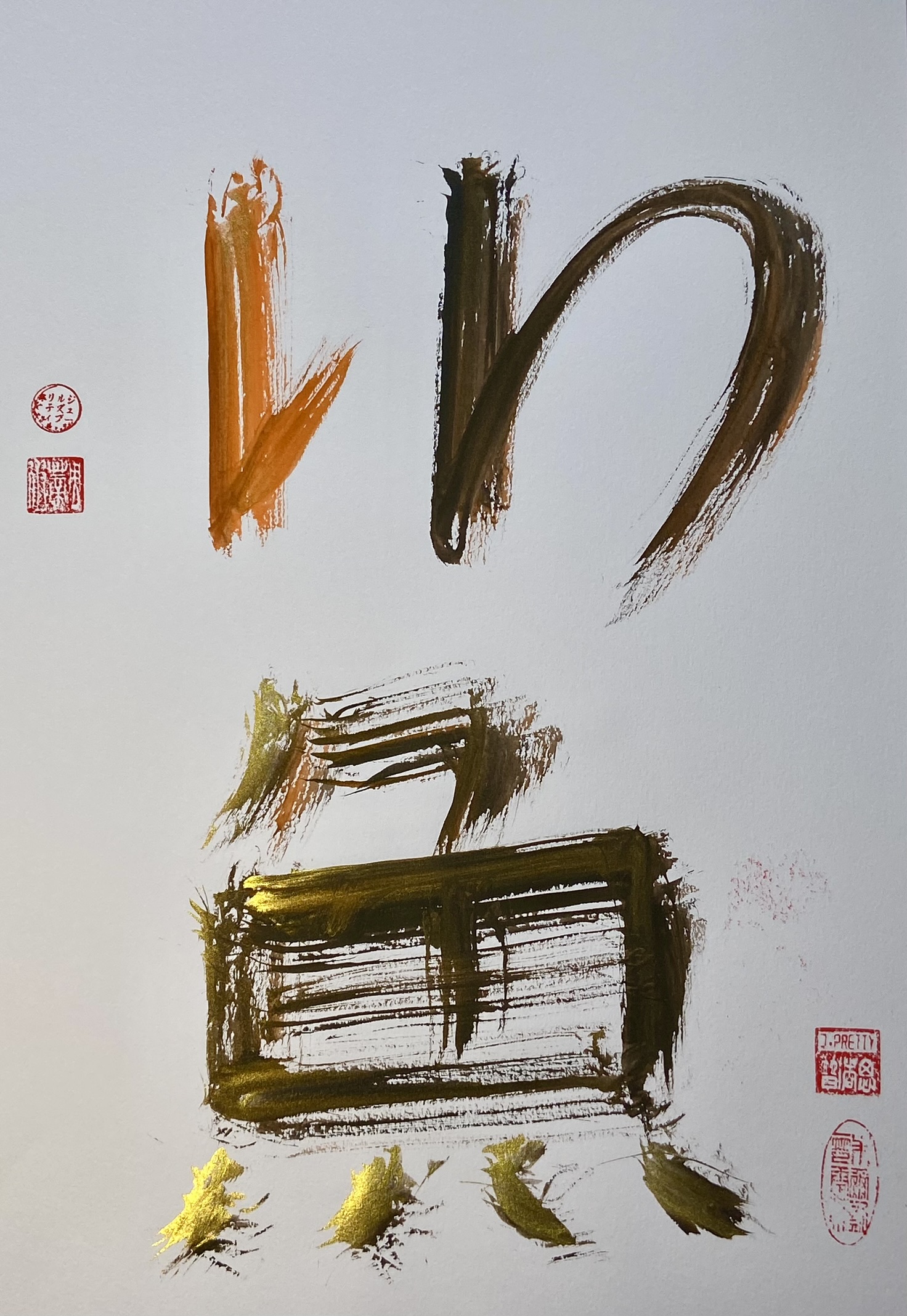

Ru Sen Man Gyo

Along comes the young girl called Guðrún, daughter of Osvif.

To the rescue.

At the time of the hay harvest, the sun always shines.

The old fighting man called Bersi the Dueller is laid out on a wooden bed beside the baby Halldór. Bersi has become badly ill over the summer, and is having his bones warmed. He’s singing to the baby.

There is distant laughter, the rhythmic swish of scythes. Bees hum, the salmon splash in the shallows. There’s the distant bleating of sheep.

All is well in the world. Until Halldór’s cradle tips, slowly to one side.

Over it goes. The baby rolls out on the meadow. Each of them is all alone in the world.

All around is great richness, buttercups and purple harebells. Yet this afternoon, they both are stranded. Bersi can only continue crooning from his bed:

“Here we lie, flat on our backs,

Halldór and I, helpless and frail,

Old age does this to me, and youth ails you,

You’ve hope of better, but I’ve none at all.”

The sounds of the hay harvest carry on. They’re over in the far fields, and the sun dips suddenly into clouds. It becomes darker. Still Bersi quietly sings, and still the baby boy lies gurgling on his back.

A group of gossipy men passes around the back of the farm, on their way to cut timber for a ship. Two are talking of a tafl game. The voices of three girls are heard too, speaking of arm-rings they’re sure to get when they are married, maybe silver and even gold.

Guðrún has already been called the most beautiful girl in all the dales, maybe in all of Iceland. She starts running, races to the rescue, picks up the baby, sings to him. She holds one of Bersi’s hands.

After a while, Bersi asks her to fetch a small wooden box, from the kitchen. This he has nursed from the isles far to the south, a gift from a princess or a queen perhaps, he never said.

He gives to Guðrún three ribbons, each is laid on perfumed paper. She skips in the grass, ties the red one into her hair. The sun breaks through the low cloud.

By now two infants are wrestling, another girl is playing a flute. There is an old white horse in the paddock by the church.

There will come a time when everyone will hear of Bersi and the baby. And know too the story of Guðrún Osvifsdottir.

It is a tale of renewal.

Nature once was plentiful. Then it wasn’t.

The seas are filled with fish. Then they aren’t. Birds sing, become silent.

The River Laxa long has flowed through their lovely wide dale down to the fjord.

It was named a thousand years ago. Each summer, salmon swim in and up. The clear waters rush over riffles, there are sheep in the pastures and the farms are well.

Many sheep.

When one farmer drives his sheep to market, the first animals arrive before the last still have left the meadows. This is the farm where Hallgerðr grew up, she who later becomes the wife of Gunnar of the handsome Hliderendi slopes. In this dale is held a feast for a thousand guests, one of the largest gatherings ever in the country.

The people call this vale Running Waters Full of Fish.

A famed saga is written about the people who live here, their lives and loves unfolding over two hundred years. The story spirals round events and people. No one is sure who wrote it.

In later life Guðrún becomes a nun and anchoress. Still blue-eyed with high cheekbones, fair but not tall.

Her life has been a story of connections, a web not separation.

She tells the story of the people and the vale. It begins when Unn the Deep-Minded arrives by longship from the Hebrides. The winds are strong, and she loses her comb as they came ashore on a promontory in a great fjord.

This place becomes known as Kambsnes, and she becomes the female leader of a great family estate. Five generations later the extended family tree brings together Guðrún with Kjartan and his foster brother Bolli.

Guðrun’s childhood is at the north end of the fjord, on a farm in a hanging valley. The place with the perfectly round hot-pool, a circle set in stone and ringed with well-fitting stones. It stands there still, steaming in the Arctic air.

Many a time, when they are young, the three sit in the stone-lined hot-pool. They laugh. They are the closest of friends. Events show she is shrewd, articulate and generous. It seems this place of plenty makes people kind, though not aways.

Guðrún becomes a famed healer, she knows the qualities of every plant. How the mountain avens was best drunk in tea infusions, how it is has the power to attract wealth from the earth.

She has four renowned dreams, is married four times. She lives to a great age, yet it is Kjartan she never marries. One day, Guðrun says to then husband Bolli, I have spun twelves ells of cloth this morning, and you, you have killed Kjartan.

Yet the web is still so strong, it is not going to be entirely teased apart by conflict.

Guðrún famously says to her son Ingunn, not yet blind as she became, “I did the worst to him I loved the most.”

“Such quarrels,” says her son.

Well, this was why she left the dale, joined the monastery at Helgafell, the holy mountain to the west.

Now the writing surely finds her. She falls upward as an elder. She feels she’s been walking in shoes too small. Now she lets those feelings go as the world expands all around.

She sets out from the known, all the excitement of dreams and marriages and lives and deaths of friends. Now each morning she walks up the mountain, whatever the weather, however many barrelling mosquitos.

Each day is different. Her soul is a warm sea. At the top is the gorgeous view, the whole round world laid out below.

The panorama is lake and marsh, drumlin and pasture farm, a thousand isles and vast swan flocks roosting on the open waters of the side-fjord. This is their place for a luminous pause between migrations, seven weeks and all of them with their flight feathers lost. This is why so many writers come here, gathering quills.

To the north is the Assembly mound. To the far east her old farm and pool, and Laxadale itself. It’s a wet world of dark stone cliff and the water turning blue when the spring sun shines.

This is the fjord known for wind and whales, risky currents, strong salmon.

She is such a keen listener that trees lean toward her.

She becomes a great story-teller.

It is an act of generosity, to tell a story of renewal. Guðrun comes to know of alchemy, she creates assets that will last a thousand years.

She turns little bits of rubble into gold.

Jules Pretty

[Ru Sen Man Gyo]

Commentary

This chronicle centres on the idea of abundance. Nature was plentiful and rich, and so it can be again. It’s just that we chose to do something different for the last couple of centuries.

We might observe we now live in a modern era of scarcity. Scarcity of attention, play, laughter, listening. Abundance just looks and feels better.

When damage is done to nature, then it is also social systems that become unravelled. Abundant salmon in the river mean successful living. They bring nutrients from the oceans, and donate protein to the rivers and the people. In Alaska, most of the nitrogen in trees originates from the oceans, carried upstream by the fish, and then into the forests by bears. All is connected.

We may feel helpless in the face of losses, yet hope holds out a prospect of divergent future paths. Thus the commentary from Bersi could work for another ten centuries hence. We lie helpless, yet hope creates agency.

If we get the systems of use and care right, they could again be self-sustaining.

There are no ruins on the plains below Helgafell, for no farms there have been abandoned.

In the Landnamabok, the foundational book of names of farm settlements, there are 4560 farms listed for all of Iceland. A thousand years later, there are still 4500 farms. Not many industrialised countries have seen such sustained rural and cultural stability, where place and identity have remained so strong.

No one seems certain who composed the Laxdaela Saga, so why not Guðrun. She was at the monastery for the last decade of her life, and we know her son Ingunn had asked her who she loved the most.

No wise person, it has been said, wishes to be their younger selves.

What is the most important quality of being old, the Dalai Lama was asked?

Cheerfulness, he replied.

Jules Pretty

Jules Pretty