[4 mins reading time]

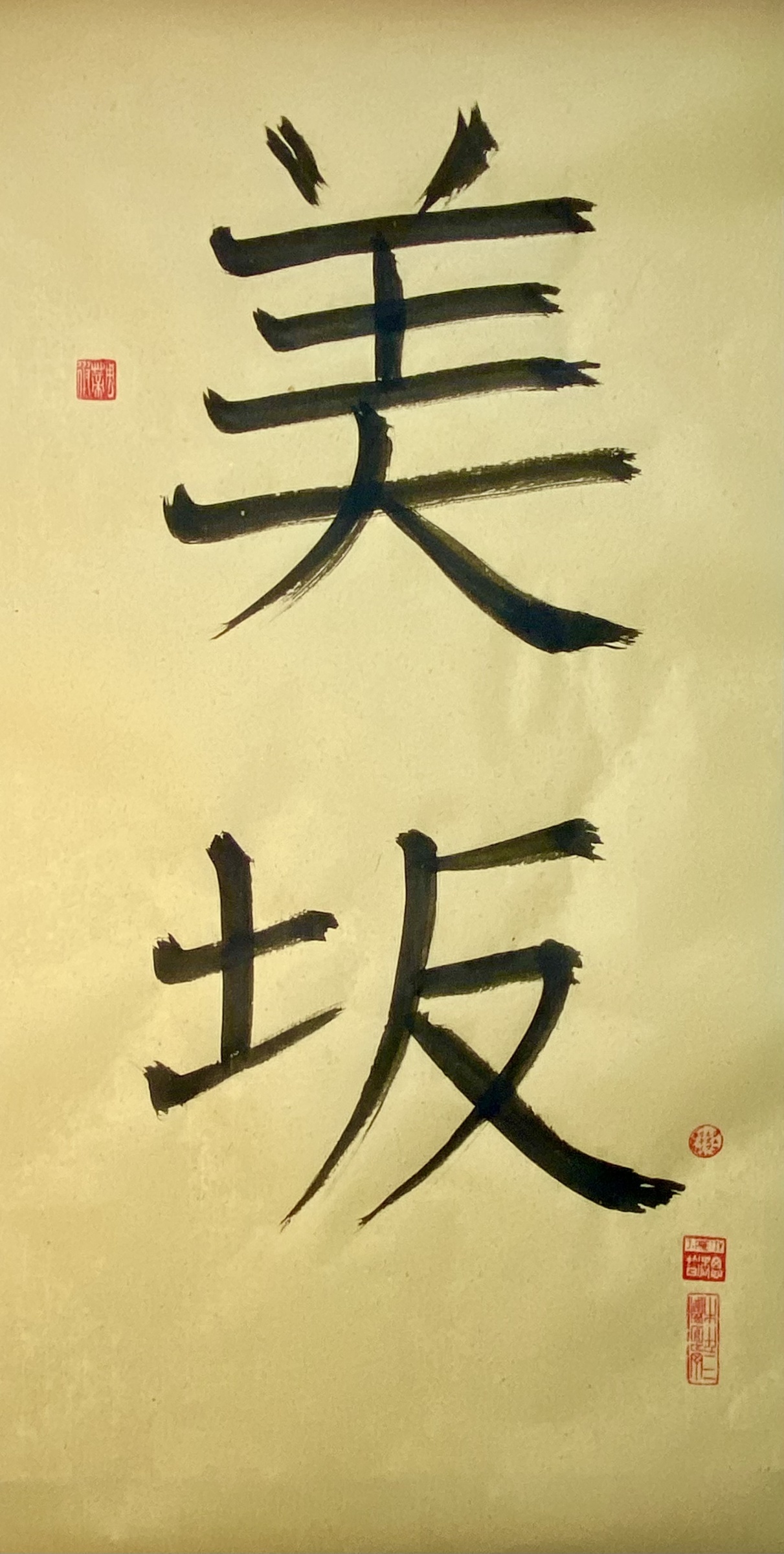

[Bi Saka Mu Kyo]

Gunnar of Hliderendi says, “The slopes are beautiful.”

“I shall not leave.”

The old sagas had something to say about coming and going. About how places grow on us. How they settle gently with emotion into memory. How we come to want to save them.

Perhaps a place doesn’t seem like much. A hill by a wet plain, a farm with a view of far mountains, a modest woodland of pine and fir.

An Icelandic saga describes their southern coast this way: “Nothing but sand and vast desert and a harbourless coast, and outside the skerries a heavy surf.”

Across the plain from great glaciers flows the Markafljót, the Mart-fleet, a great interlace of river that takes to marshlands and skirts his slope-land farm.

Gunnar is well-known for his sharp eye, his wife Hallgerðr for being able to pick an argument with a rock or tree. Their friends and neighbours are Njál and Bergthora: both will be burned, unfairly attacked, their deaths across the flats at Bergthórshvoll.

These days the electric ferry from the Westmann Islands docks at the new harbour. A track crosses the plain on ridged roads of ash.

And there at the apron base of the slopes at Hliderendi is Reyfar the Fox, dressed in summer fur.

He’s sitting by a cattle grid on the dry road. All around is the mutter of water rushing off the slope.

“Lovely is this hillside,” says Reyfar.

“It has always been this way. Welcome and come long.”

The next thing Reyfar the trickster says, for this is his role, makes you stop.

“There are enemies too, and only some are ghosts. Some are at the crossings on the moor, they will be in the river valleys, they are in the factories and in the warming skies.”

So it is that any journey across a fine land can be halted, beaten back.

The trickster takes you up the hill to Gunnar’s mound, there by the bracing copse of pine.

When the moon is full, Gunnar’s figure is often seen, sitting in the open air and smiling. By the old platform for his farmhouse, by the barrow. He and his wife still hold hands and beam at the view.

They are sticky ghosts. They resolved never to leave their green slopes of home.

The seas are lovely too. The whales did not need to leave either.

Nor the geese and swans, nor fox and salmon, nor smaller fishes at the shore. It was not written that the road to Ragnarök should advance so fast. Or even that it should happen at all.

On any given day, there might be terrible heat and tremendous winter, and the one last giant battle. A person in a cave or under land can end up being quite a bit unhinged.

You would think the same of Gunnar and Hallgerðr.

Yet they are here on bright nights, looking round at the slope and view, at the wooden church with white walls and red corrugated roof. The very church walls pock-marked by hot ash from the Eyjafjallajökull eruption, the one that closed the skies of Europe.

Gunnar is blue-eyed, so swift with a sword it seems like there are three people in the air at once. He has blond hair, is a little thin now, and swims like a seal. Hallgerðr is still beautiful, her hair fine as silk, it comes down to her waist. None of her nails are chipped. The saga says she wants to be the centre of attention, she’s not so even-tempered as Gunnar.

They both loved Sámr their dog, so warmly greet Reyfar whenever he brings visitors. Samr was slayed at this very home by jealous neighbour Morð, the same night as Gunnar was killed.

Forty men come down the hollow road to the farmhouse from the fell pastures. They entice his dog Sámr away. Gunnar says, you’ve been cruelly used, my foster-child Sámr. It is expected our deaths are meant to be close together.

Some say Gunnar ought to have stayed away. But here he is.

They are attacked, he repels them with his bow, he injures fourteen and kills two, but his bow is cut by Thorbrand.

Gunnar’s friend Njál buries him in the mound. Even when dead, Gunnar still has to see the magic of the southern light on the hills.

Gunnar says:

“How lovely the slopes are,

More lovely than they ever seemed to me before,

Golden cornfields and new mown hay,

I am going back home, and I will not go away.”

[Njál’s Saga]

So now Gunnar and Hallgerðr stroll with Reyfar round the slopes in the evening moonlight. They beat the bounds. A cool wind rushes down the valley.

They all are as cheerful as can be. The minister at the church, he calls a greeting from the porch.

Gunnar waves, continues walking around the meadow.

Not so much has changed in a thousand years.

Jules Pretty

Commentary

Trouble today is brewing.

The world’s heat has come to places distant from the main sources of pollution. Places and nature are being sacrificed for material progress.

The earth, it could be said, needs more of us to recognise how lovely it is, and to state we will not leave. We should not let the bands of forty thieves led by modern Morðs take it all away.

Story and saga have a role beyond entertainment. They are also a way of looking after places, giving them a sub-song of emotion and meaning that could last across the centuries. After all, people have been hearing about and coming to Hliderendi to see the farm of Gunnar and Hallgerðr for a thousand years.

A century after the settlement of Iceland, there were 4560 farms. Today there are still 4500. Not many industrialised countries have managed such stability of rural places.

The koan question may then centre how the particularities of each place can be made special, and how this could help in conservation and regeneration.

Let there be fog, let there be ways past the trolls, for there will be wondrous sights for all who follow.

And Gunnar says, be careful, for there always were thieves and rogues on the road, ready to steal your land and places away.

Jules Pretty

Jules Pretty