[5 minutes reading time]

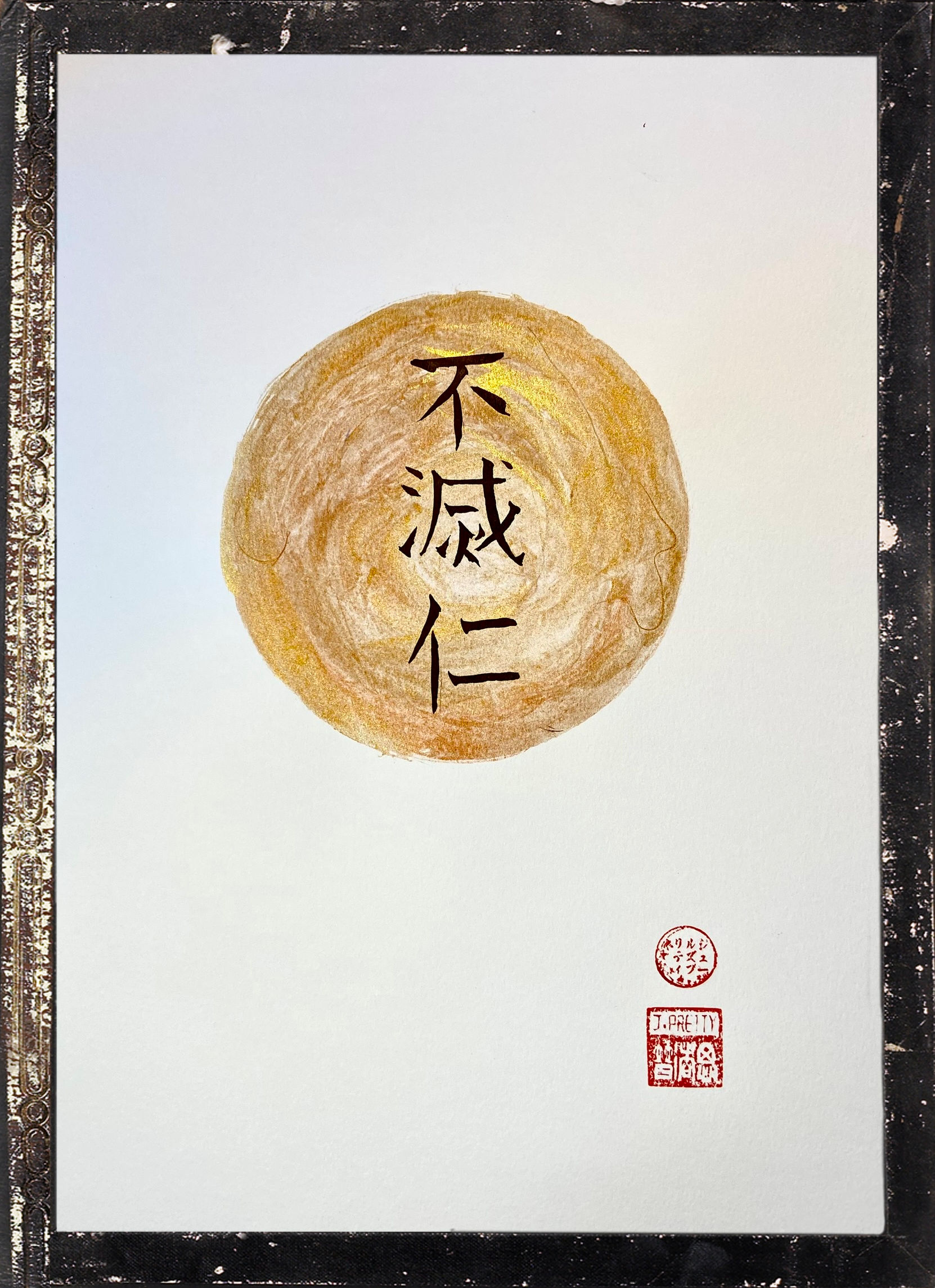

[Fu Metsu Jin Ni: Indestructible Kindness]

The longship is tacking. It heels toward the shore.

The square sail fills, the hemp ropes straining on the blocks. The clinkered hull cuts across the shallow sea.

On the skyline are two towers. A chief’s hall, a longhouse placed just so, its two tall chimneys when aligned pointing to the safe lane into the harbour. The ship races south. The sun shines and the sea glitters, the planks creak. Gulls cry, and there are other sail-steeds on the sound.

The crew can see, it is a country of healthy communities, smoke from many hearths clinging to the hills.

The hull is stacked with war gear, axes and swords. A dragon is painted on each linden shield. A coastguard watches from the shore, wondering whether this ship is fair or foul.

This ship strides so fast. It does not rise and plunge, so in the hull are ballast stones of granite. The bow and stern flexes sideways, the ship shifts energy from sea to forward movement.

There is no keel, the crew just move from side to side.

On a hillside mound is a copse of pine, the kind of place where a longship is entombed and a dead king laid on fur, a sword in hand, a shield laid by their side.

The wanderers point, for the outcrop shrine is named after a famous seafarer of old.

There might be gold interred, so from the fjord below sailors look up and steer a little nearer, their sails stiffened by the breeze.

West across the brine and up one estuary, not as wide as this, is the buried longship of Sutton Hoo, half a league uphill and laid in one of twenty mounds. The king’s hinged helm of tinned bronze has a dragon stitched across each brow. It was such a golden Saxon burial that many felt he may have been as famed as Beowulf, the Geat warrior-king himself.

And Beowulf is sailing here because of horror.

It’s being visited on Hrothgar’s Hall at Heorot. Beowulf has come from far to offer help.

His ship’s been flying like a bird, the wind behind them, foam at her neck. Now the skipper smiles, oars up he says. Painters out, the rattle of pine in oarlock ropes.

A girl and small boy sit on a rock, watching from the shore.

Silence, then dip and splash, creak and splash again, and the ship glides to the beach. The breeze drops and the air on land is hot.

Some leagues south and west of here, a brisk march away, is Hrothgar’s court at Gammel Lejre.

And in these low-lying lands of Sjælland is many a mere and marsh, perfect lair for troll and ogre, a source of every kind of sorrow.

At Lejre, dynastic home of the Scefings and the Sjoldungs, the people of the sheaf and shield, is the folk-hall fifty paces long. There are outbuildings for craft and prayer, the rich burial mound of Grydehøj.

Heorot Hall has a world tree just like Yggdrasil, its branches and blossom up inside the roof. Cloud often forms in the rafters.

The hall has tiered side-benches where people sit and sleep, facing cross the fire-stones. There are treasure chests. The roof is shingled, there are covered walkways beneath the eaves.

At this place ruled both Hrothgar and Hrolf Kraki, the most magnificent kings of ancient times. And here too come the bear-men, the bee-wolfs, Beowulf and Baldar Bjarki.

Of all the ghosts of admirals and kings, Hrothgar is the wisest king, but nothing he could do kept the monsters in the mere. Yet Hrothgar did not blame his people for their misfortune.

He could not protect his hall from Grendel and his ogre-mother, yet did not lose his people’s support.

Hrothgar speaks of the dangers of all power, particularly as there will come a time when the old powers seem only paltry:

“A man in his unthinkingness forgets, that it will ever end for him.”

The epic poem seems a famed tale of terror, yet some say it is more about togetherness and kindness. After Beowulf battles Grendel, this lonely demon, the order is given for all hands to refurbish Heorot.

The poet says:

“Men and women throng the wine-hall,

Gold thread shines in the wall hangings,

The benches fill with famous people,

There is nothing but friendship.”

Also writes the poet:

“There haven’t been many moments, I am sure,

When people exchanged such treasure at so friendly a sitting,

They sang then and played to please,

Words and music, harp tunes and tales of adventure.

Applause soon filled the hall.”

Hrothgar the King believes gold does no one much good. The warrior bear-man Beowulf later rules the Geats for fifty winters.

It is said, “He grew old and wise as warden of the land.”

But time creeps up on him too. A long-slumbering dragon is woken by a thief. He breaks into the lair, steals a piece of treasure, unleashes all kinds of fire and anger.

The dragon has been protecting people from their greedy selves, yet dies fighting Beowulf. The old king dies too, and is buried in a mound overlooking the sea. People at the funeral tear out their hair and cry, for now they fear impermanence.

They have heard of forces gathered at their borders.

Thirteen hundred years later, men and women with magic in their fingers are fitting perfect mortice joints, smelting iron for nails.

They are building longships, at the Roskilde shipyard. In the modern museum of shuttered concrete, the sea slapping at the base of windowed hall, are the five Skuldelev ships, propped above a floor of stones.

Their wood is bog-black.

They have sweeping lines from stern to prow, on one of which is placed a golden dragon’s head. These ships were found twenty leagues north, raised from mud. They had been sunk as a defensive barrier to prevent attacks from sea.

That may have been an act of desperation, or perhaps of love, for such a longship could take a year to build, or maybe two.

All those years of silence are wrapped around each ship.

The brothers of Svipdag once asked their Swedish father Svip what King Hrolf Kraki was like, the wise king of Sjælland isle who ruled after Hrothgar?

“I have heard he is open-handed and generous,

He withholds neither gold nor treasure,

He is fierce with the greedy, yet gentle with the modest,

He is the most humble of men, so great,

His name will not be forgotten, as long as the world remains inhabited.”

[Snorri Sturluson, The Prose Edda, 1179-1241]

Jules Pretty

[Fu Metsu Jin Ni]

Commentary

The koan Fu Metsu Jin Ni translates as Indestructible Kindness. Beowulf comes to help Hrothgar and his people. His currency is reputation not treasure. He returns with a great story, and is famed for it. He rules for half a century.

The great threats of Grendel and his ogre mother, from the shadows and the far beyond, they cannot in the end destroy the kindness.

Oliver Scott Curry at the Oxford Kindlab studied behaviours in sixty countries, and found cooperation centred on shared resources, coordination of mutual advantage, social exchange, conflict resolution, fairness and loyalty. Of 962 observed rituals and behaviours, 961 had positive moral outcomes, leading Curry to suggest these looked like laws or human universals.

Rutger Bregman in his book Human Kind said, “People, deep down, are pretty decent.”

Bregman also detailed the work of the Delaware Disaster Research Centre, which studied 700 examples of disasters worldwide since the early 1960s.

In the overwhelming majority, people were actively prosocial. They did not go into shock, they stayed calm, and sprung into action to help others. Each year for the past decade, the Charities Aid Foundation has produced a World Giving Index. It ranks countries by asking three questions: in the past month, have you i) helped a stranger, or someone you didn’t know who needed help; ii) donated money to a charity; iii) volunteered your time to an organisation? More than three in ten adults around the world donated money to charity in 2020. The top ten countries in 2020 were Australia, Ghana, Indonesia, Kenya, Kosovo Myanmar, New Zealand, Nigeria, Thailand and Uganda,

It seems kindness is both our common state and response to threat. It is selfishness that is the outlier.

Towards the end of the epic poem, Beowulf has to fight a fire-breathing dragon. A thief had found the dragon’s mound, and stole away a golden cup.

Yet dragons weren’t hoarding, they were protecting people from themselves, keeping the riches hidden and preventing conflict. This dragon marks the end of Beowulf’s reign and life. At his funeral, people tear their hair and clothes, for they realise forces are now gathered at their borders.

It looks like things are about to get worse. What we wonder will prevail in the face of disaster? This is the topic of the koan.

Gary Snyder translated chapter 33 of the Tao Te Ching in this way:

“The best things in life,

Are not things.”

Jules Pretty

Jules Pretty