[7 minutes reading time]

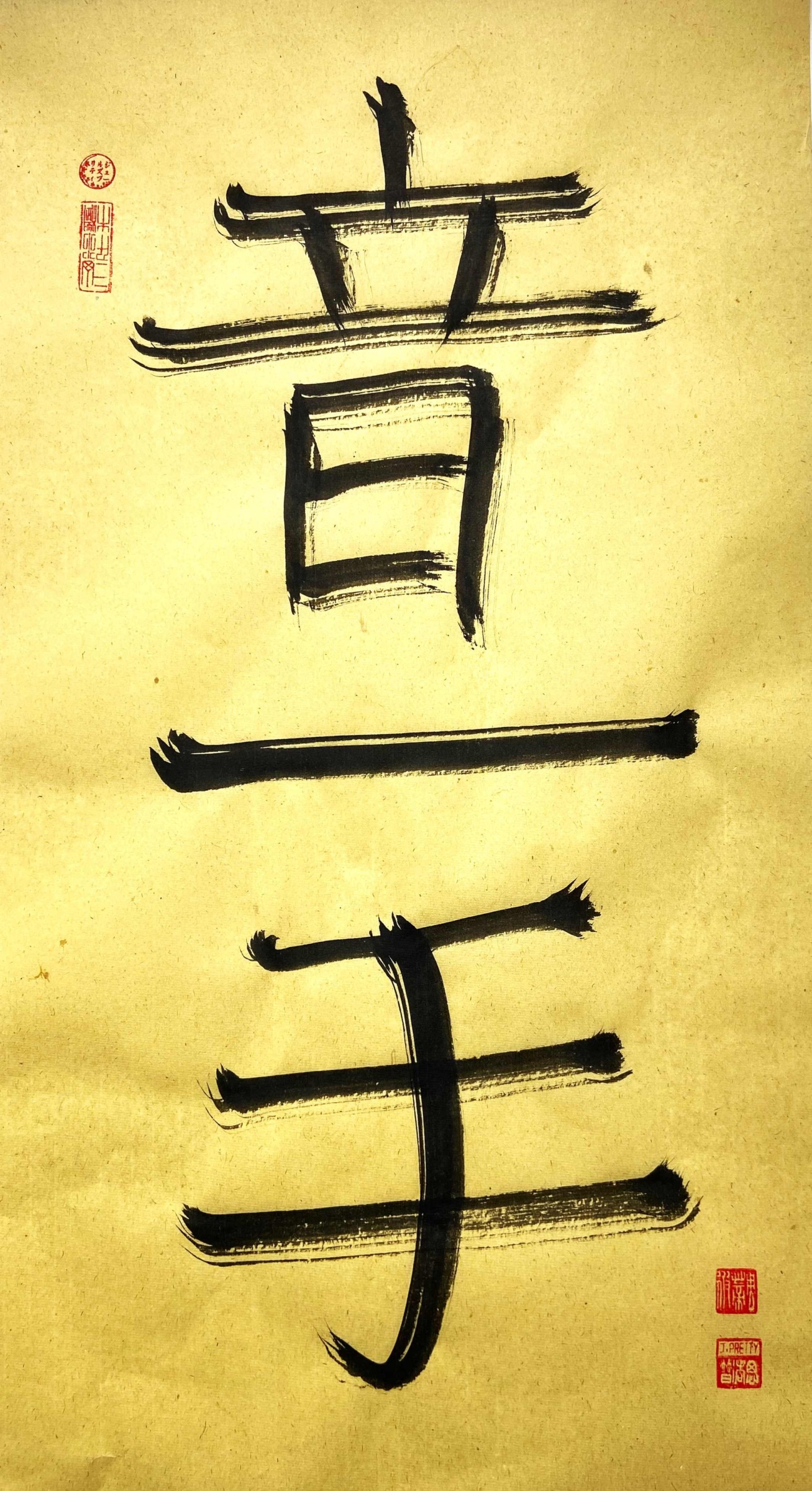

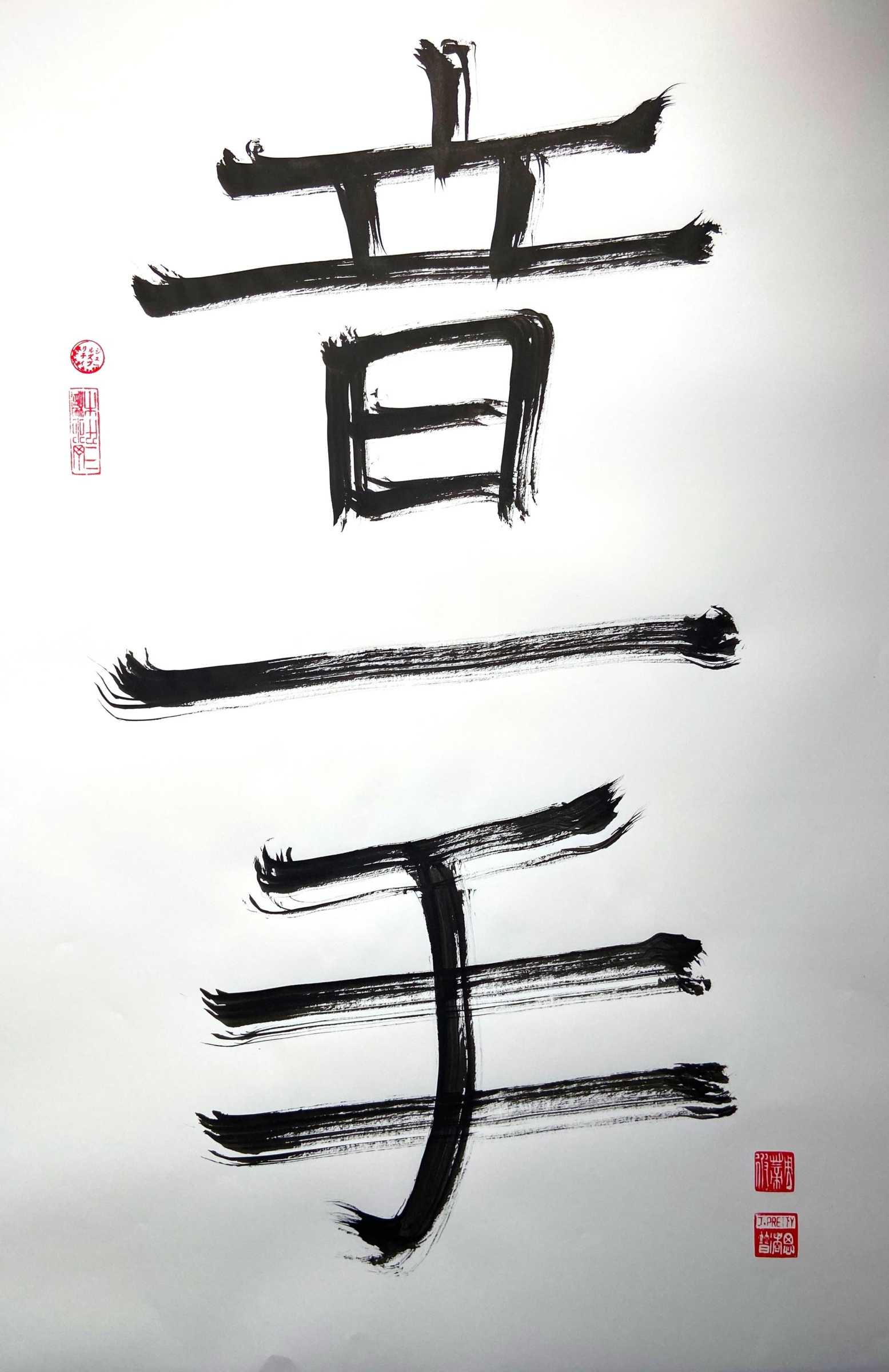

On Ichi Shu [The Sound of One Hand]

The word about town.

This girl Skaði has it.

She knows when to watch. When to keep silent. She knows when to raise a hand, or just leap right in.

One hand opens a path into the world. It moves the air. The water too.

It can be quite silent. Quite attentive.

Skaði lives on Flatey, the flat isle. A place of learning and writing. A place of skerries and rocks and treacherous sea roads. To the south, on the mainland peninsula, the regional Hunavatn Assembly point. Beyond that Helgafell, the Holy Mount.

Skaði is a tough swimmer, living by the shore. As are the men who carry oars, who bend their backs for pay on the sea-going longships. She wins countless challenges, when many a man first pushes her underwater, tries to hold her there. And then she’ll press them down, stronger than their struggles. Till bubbles stop.

And then she sets them free. Spluttering and red-faced.

What good is this, they say, in so many words. You’re just going to be married off.

She can’t shake off the feeling she is waiting for something else. She just knows it’s not this.

If any ship is wrecked on the skerries round the isle, Skaði still leads the swim into the wreckage.

One day a ship approaches, struggling in a storm. All on board, they throw away everything to stay afloat. Yet a giant breaker rises where no one could recall having seen rocks. It swipes at the ship, smashing planks to pieces.

Skaði swims to the wreckage, three times she tows a sailor ashore.

From an early age, she has lovely eyes, a fair complexion, hair shiny as a silken scarf.

Her father is proud.

Her’s is a tale of quiet transformation, about crossings from one place to the next, from one stage of life to another. She is a grand-daughter of a famed Iceland settler, he’s called Ingimund. He crosses the sea to lovely Vatnsdal, a dale wide and green, and builds a longhouse one hundred strides in length.

Such migration is an imaginative act. You have to think: what will it be like when I arrive? How will I feel? Iceland is appealing to migrants. No king, a decentralised commonwealth, land without political memory.

Where there’s a kinder and gentler way of living. Except not everyone thinks that way. Some come to find gold. They’ve heard the stories.

In summer it seems the days are always cloudless, there are fish in nearby lakes and river, the livestock feed themselves in winter. Now comes the family member Hrolleif, he’s going to break their hearts in half.

Days and years pass. The clan of Ingimund grows settled. He is wise, voted speaker of the Hunavatn assembly.

Yet the sense of menace develops. Hrolleif wears a wine-red cloak, is nimble with his sword. He walks through other farms as if he owns them, yelling insults at the daughters. The valley people soon suspect there must be robbers on the pass, for certain travellers seem to disappear.

One day Ingimund’s younger brother Odd and three fellow farmers are found beaten and bleeding by the river.

Hrolleif and Kör his wife are outlawed. They flee west to the windswept isles, where by then lives the girl called Skaði. Her mother’s name is Fenja, she has countless skills. She heals ills, dispatches disease and sores. Egil is Skaði’s father, the youngest son of Ingimund.

But Hrolleif too is growing stronger. He builds his fire-hall longer than any on the isle.

The son of Hrolleif and wicked Kör seems to some to be a troll. He grows wide as well as tall, and now the local people fear their worlds will be upturned. No man with axe or pike can find a way to challenge any of the men at Hrolleif’s house.

So they turn to Fenja, plead that she call on spirits to cleanse their isle. To rid them of this tribe of trouble.

Egil has a fine herd of horses, bred with coloured manes. One day in late spring, when a thick fall of snow has covered fields and fells, he and Skaði are stranded at a distant farm. And Fenja is left alone to fight the evil Kör.

It’s bad. Local shepherds hear thunder crashes from the hall of Hrolleif.

When the sun rises, the people find a rock fall has crushed the hall. And yet, they can find no bodies. At Egil’s house too, the fire grate is cold.

Yet not everyone is dead.

They find the hulking troll-boy stunned upon the shore. He’s been shouting loud enough for all the rocks to hear.

There’ll be no more of this. His days are done. He’s going to feel like prey now.

News reaches Egil and Skaði. A black cloud descends.

They ride hard. The sky brightens, but prospects still are dark. Skaði’s fixes a leash-spell. She releases all Kör’s cats from bonds. They flee into the fields.

Egil is bent and broken, Skaði too.

Egil says, “I think you should go alone. Take the troll-boy, to the law rock.”

“You are ready. I’m sure your mother would agree.”

“You will find,” he says, “A hundred flags flying on the plain beneath the rocky row of pillars. This is your calling now.”

The moon waxes. It wanes. The month of the summer Althing approaches. Orchids are in flower. There are melancholy calls of loons out on water.

Now Skaði steps across the threshold.

This day the sun is hot, though shadows seem to come from winter. Hare’s tail bobs on marshes filled with sky. At bilberry slopes a whimbrel burbles, the plover sings insistent warnings.

Snow lies on the taller ridges.

Skaði whistles out a call, a gloss black raven caws and perches on her shoulder. In her basket she has her potions. In her mind she holds more charms. Now they bend their steps past sulphured banks of bedstraw.

The polar light is brilliant blue, water glistening over riffles. It is the month for cutting hay, and distant men and women swing their scythes, singing to the vernal grass.

Every farmer aids every neighbour. Wind and rain await. They hurry in the sunshine, for it could be winter in an hour.

Skaði’s sure this troll has never helped with the hay at any time.

They cross a plain of steam, water gushing into sky. She stands upon a rocky hill. Ahead is the plain of snapping flags. At booths of stone and turf are the waiting goðar farmers and their thingmen.

Cod dries in the polar wind, on stokks of wood.

A herald blows his horn, the lowing echoes off the rocks, rolls across the flats.

An eagle flies to its eyrie, perches and looks below. To see the throng is opening up, for this single girl.

She knows the path. Their plot is by the Lögberg. Where the Lawspeaker will be calling from his memory one third of all the laws.

She’ll leave to them the task of serving justice on the killer. He’s now tied to a post. The roped man’s final crossing made.

To succeed at the Althing you need charm. Skill with words to manage feuds, this she’s learned. Her tent is pitched before the colour riot. Yet servants bow their heads, for in former years here had stood Fenja, helping each person in the queue.

Skaði steps inside. Looks around, claps her hands.

The men and women cheer, call out Skaði’s name. She is keeper of the magic apple, speaks to Oðinn’s Ravens. Swords thump on shields, they point to their ill.

She smiles and nods. She raises one hand. Then the other.

All fall quiet. The only sound: the flags on spears are snapping in the warriors’ hands.

Soon she’ll walk from booth to booth. One hand raised for silence.

This girl, you know, she’s on the way.

Jules Pretty

Commentary: On Ichi Shu [What is the Sound of One Hand?]

This is a famed koan partly because it seems so odd. It doesn’t seem to have an answer, particularly if we find ourselves thinking of koans as riddles.

The use of a koan here is to open up space. It is a dark forest of a question, a high cliff, something that looks impossible to navigate. One hand, after all, produces no sound.

Yet we might think of sound as a call. Nothing in nature should need to call out in vain. There is always someone, some path or way, waiting and listening. What does the world look like if it becomes filled with unheard calls?

One hand can only be silent, and so we could enter into vast stillness, holding ourselves closer to life itself. One hand opens a path into this world. It moves air. We could look behind, or underneath. We could let the one hand open a way into a new life. Not good, not bad, just as it is.

Fortunately, Skaði was a listener and attentive. At a low ebb, she walked to the Althing, the great democratic gathering in the open air at Thingvellir.

A new life awaited. That was the sound of one hand.

Jules Pretty

Jules Pretty