[5 minutes reading time]

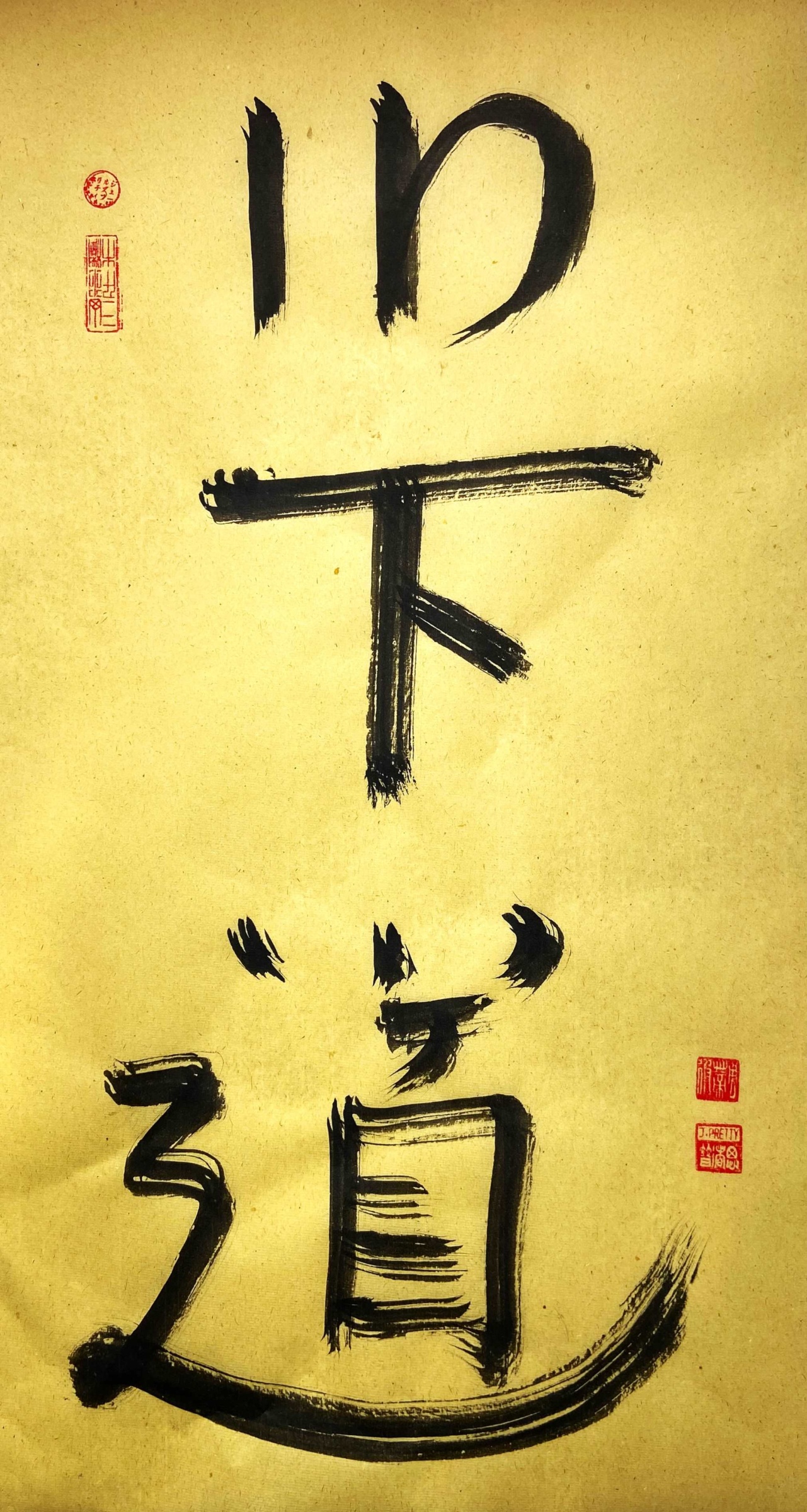

Sen Ka Do [River Under the Way]

A year is ending. A whole receding era.

The fish are hidden, the water veiled. The sky is far beyond a bitter blizzard.

So in a way it is breathtaking to gaze below the ice. Spy the slowly rising treasure, all silver and glittering. And see half a thousand shadows somehow cast upward on a thermocline.

Before dawn the fish crew, towing sleds behind each skidoo, leave behind the lake-side factory lights. Headlamps bounce, there seems no compass point, nor sign of distant trees. Yet in the hollows, slush is puddling, pressing down the ice.

All is clamour, nothing close to normal.

Esa Rahunen the fisher-leader, the wind at his back, weaves this way and that, calls across and waves his arms.

“It’s never been this warm, not in mid-winter.”

He points to a place, a skidoo was there and abruptly sunk.

They have lost a month of ice. At the start and at end of the normal winter seining season. The old normal has gone.

At his home the night before, in the taiga forest, Esa unrolls the sacred family map. Puts down salt and pepper pots, two mugs on other corners, this chart of the Puruvesi lake system all in fine-grained detail.

So wide it is, it has its own weather systems.

In old script are marked a hundred seining sites. This mesh of secret apaya, this is the way of once eternal ice.

You have to learn about each place, you have to know five landscapes. The seabed and the water column, the rough lower surface of the ice, the ice itself and warming air above.

Yet Esa still has to dream. He has to find how the vendace fish will choose themselves a site.

So each night he closes eyes, and soon the fish will be there. And then by day the fishers will watch. And listen to the ravens.

Outside in the forest, a frozen branch cracks and falls with thump.

At the centre of all the Norse world is Yggdrasil, the tree that holds up the sky. The sagas of Finland also begin beneath a tree, the giant pine at Hummovaara meadow.

Here a district doctor sits with a seine fisherman, Juhana Kainulainen. He’s a hunter and a tietäjä spirit man. Kainulainen dictates to Elias Lönnrot more than two thousand lines of oral poetry. These become The Kalevala, an epic that moulds national identity.

The great pine still stands alone on a rise, taller by a half than any other tree. On a winter day, the snow is deep and the taiga cold and long. The afternoon sky is often fiery pink.

According to tradition trees have strong spirits. Before cutting, it is best to knock on a trunk with the handle of an axe. To ask the spirit kindly to leave. Another practice: cut the branches in a set pattern. As the tree grows, so gaps will always remain, telling their story.

There was a time when authorities called these suspicious trees. They speak a different language.

It’s before dawn.

On the icy sphere, a chainsaw roars, cutting one slot, then another a thousand paces distant. At the ice holes, the fishers peer carefully at the ice. Too many air bubbles to be strong, too many warm periods this winter.

Fine nets that crack with ice are dropped into the underworld. Each is pulled by cables, for six slow hours in the winter twilight.

Now an ancient practice. These seine fishermen are tradition-bearers, practices continued over a thousand years and more.

Olli Klemola is an elder, a winter seiner from the west. A shaman too. He’s wiry, fierce blue eyes, beard already icy. It’s been sad, he says. The damage over his lifetime brought by the age of machines.

“When you have a certain knowledge of nature, you have awareness, and then you start to see,” he says.

“How beautiful is the system when you are alone in it.”

He talks of catching turbot in deep winter. You walk quietly out on the ice, lie down, wait as you absorb into the water and ice and air.

Then smack.

You hit the surface with a hammer in this way. The fish beneath is stunned. You make a hole and pick it out.

“This is the way: to be eye to eye with the fish.”

“It is an in-born feeling. I know where the fish are.”

“My mind is very clear,” Olli says. “I’m just being inside nature.”

He picks up a finger-sized salmonid, flipped up by nets and frozen.

“Eat it,” he says.

The fisherman’s oath, says Olli turning to the others. It’s cold. The blizzard continues.

Two gloss black ravens call, hop from crate to black water side.

You lie upon the ice, look down into the river of fish. And there comes the silver tickertape, upwards from the deep.

Those black-eyed silver fish soon are stunned, freezing as they meet the air above.

It is a kind of miracle, these fish who give themselves to fishers.

Now comes the market dash, back to distant factory. The lead skidoo clips a bank of ice, twists in the slush. It tips over, the driver and the passenger diving free.

A tonne of fish totters, the crate tips back upright.

Thus the fish soon are sorted, packed and loaded. The fishers give gifts away to local people waiting at the loading bay.

Well on this day comes commotion. A politician arrives. He wishes to have a factory tour, check how subsidies are being spent. He projects suspicion.

At the kitchen table, he speaks of baiting green members of parliament. He talks of trapping thieving wolves who steal babies.

The factory manager unscrews a second vodka bottle. And the statesman laughs and calls them nonsense, all those climate claims.

The fishermen twitch, glance with no more than micro-expression.

They go on sipping their by-now-sour coffee.

In mid-winter, when the days are short yet dawn and dusk are long and low, you can walk out from the fishermen’s cooperative on the banks of the great lake.

Today there is a single wisp of cloud in the sky.

It may turn into a storm.

It may leave the world blue and bright.

Jules Pretty

[Sen Ka Do: River Under the Way]

Commentary

A koan is a matter to be made clearer. It points to something of deep importance that invites us to stand in that place.

What merit had been caused? A star at dawn, bubbles in the ice. Below the fish lived freely, on their own ways as they ever did.

The fish chose to rise like thoughts, and this was how Esa selected the best apaya seining sites to fish the next dawn. On their way, the fishers themselves were comfortable with not knowing, comfortable with discomfort.

There are deep currents in the river under the way. The thousand-year tradition of collective seine-fishing. The spread of climate change.

Esa was a form of shaman, dreaming up the fish. He played guitar and loved heavy metal. One year he was looking forward to seeing the band Deep Purple, due to play in Finland’s far east. He wrote: “They cancelled at the last minute. We were too far away for them.”

On the ice-roads, said Esa, “We will be the last.”

Esa Rahunen died in 2016. That single wisp of cloud, where is it now?

Jules Pretty

Jules Pretty