[4 mins reading time]

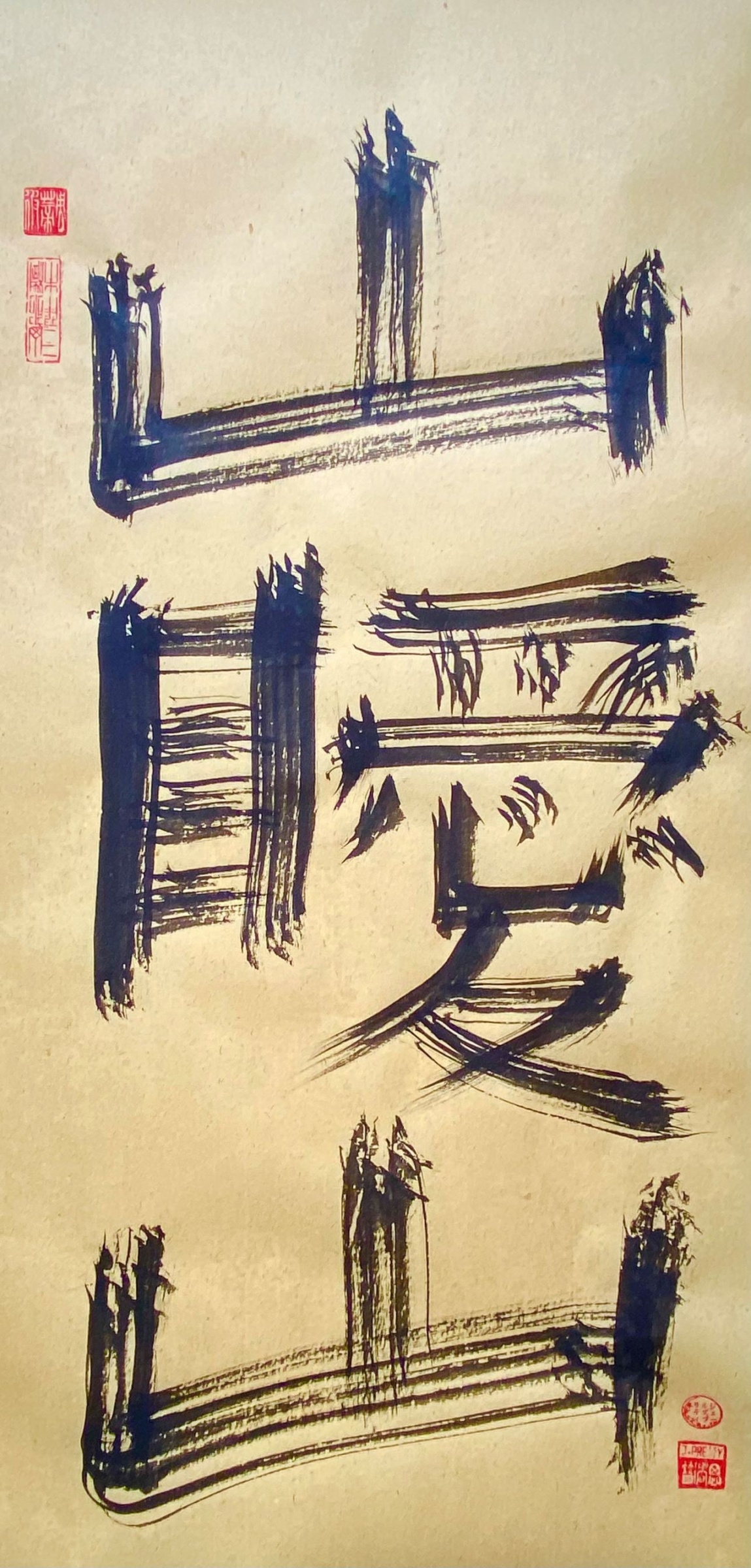

[San Hi San: Mountains Hidden in Mountains]

The Siberian man walks uphill. He comes to the mouth of the sandstone canyon.

He crouches by the rockface, makes a pile of kindling wood. Lays out types of cheese, sweet pastry, wrapped snacks.

He ties prayer flags to a pole, all bright blue and green, red and yellow and white.

He knows the shaman ways.

He lights the fire. The people stand in a semi-circle, watch as the libation burns. The smoke itself twists gently in the mountain air.

This the hidden mountain called Kezhege. It’s the place of sacred abundance.

It is where people ask for the whole thing. For cows, for sheep, for a house. For children. This is the place where wishes do come true.

It is right at the centre of Asia. By the River Tes, winding over the steppe and past ancient stone circles.

Kezhege is quiet under the high-plain light.

The band has travelled for three days.

An old plane with heat belting out from plates in the fuselage, another that sets them down in the wrong city, several cars, a horse and cart. They pass along the migration routes of sayan antelope. Skirt a high blue lentic lake, the place of pike and strange fishes stranded in these Altai mountains.

There is a band of khöömei throat-singers standing by a white minibus. They are people with a long stride, the freedom of the steppe.

The throat-singer Sayan Papa sings. It’s an ancient song of purification, the under and over tones emerging from the land itself, the centuries of life on windblown grassland and beside taiga forest, alongside river and mewing lambs. All a sonic mirror of the steppe:

“Let all the people live well, let their work go well,

Let children live well, let life be without obstruction.”

The Pamirs and the Hindu Kush are away to the south. Not far from the yurts at the lake shore is the high desert market. There are stalls for clothes and bright goods, solar panels for yurts, goods travelling this way and that across the porous border.

By night the travellers climb the dim stairwell in the cold concrete block. The space is lit by strip lights. By brighter day, there are lace tablecloths laid with cheese and potato soup, pickled tomato and beets, rough bread. There is warm broth and hot tea.

It has been another winter of deep snow yet now come sudden melts and refreezing, stopping animals from digging for the grass below.

There has been in recent times fast spring flood, parasitic sheep disease, furious grassland fire, shifting vegetation patterns.

It all makes harder work for the healers, the shamans and the lamas. The forecast is troubling.

The better course, far and wide, might well have been to keep all of nature sacred.

Now the sun beats from the wide steppe sky. Fire turns the offerings to ashes.

At the centre of the mountain is an enclosed amphitheatre.

It is filled with more coloured flags tied to bushes. High above on rock faces are petroglyphs whose stories come from a distant age. There are singing caves, when the wind blows in and out and all around. There are plastic models, house and cow, baby dolls, placed on ledges looking inward.

From this calm underworld, an icy crevasse splits the rock. The climb is vertical and slippery. All are wondering, can this be safe, how will we come back downward.

The hidden mountains always know more than we do. Their songs of bee and grasshopper are loud in the upper meadow. An arctic halo surrounds the sun, ice crystals in the altostratus.

A falcon circles over the quivering grass.

At this point, you may sit at the canyon edge.

And lift your face to the sun, shut your eyes and let the rich red colour form. Sounds will fade. Soon there will be silence.

Indeed the day hushes. Each insect and bird falls quiet. Even the wind this high up ceases all movement.

At this place, there is a kind of overview effect. The whole planet in all its beauty and connections is spread out below, the bend of the river and the mountains sprinkled white on the far horizon.

The world has come to a halt, once again.

In each such holy places of old, a song deeper than silence still is calling from the land. It comes from inside the mountains hidden in mountains.

The leader of the nomads says, “We are grateful for our isolation.”

Jules Pretty

Commentary on San Hi San

This koan says there are mountains hidden in mountains, in their sacred mists and clouds. We may climb up, on winding grassy paths or straight steps cut from rock a thousand years ago. At the top, we hope to find we can break through to blue sky and brilliant sunshine.

Mountains are themselves too great not to be hidden. They cannot be known in full. We may learn from mountains to be comfortable with mystery, with the unknowable.

Mountains are so great you cannot miss them. Yet they are hidden.

The world is full of unknowables. Sometimes we break through, sometimes not. What does it take to keep climbing?

Bashō wrote this famed haiku:

“How fun it was, Not to see, Mount Fuji in foggy rain.”

Jules Pretty

Jules Pretty