[10 mins reading time]

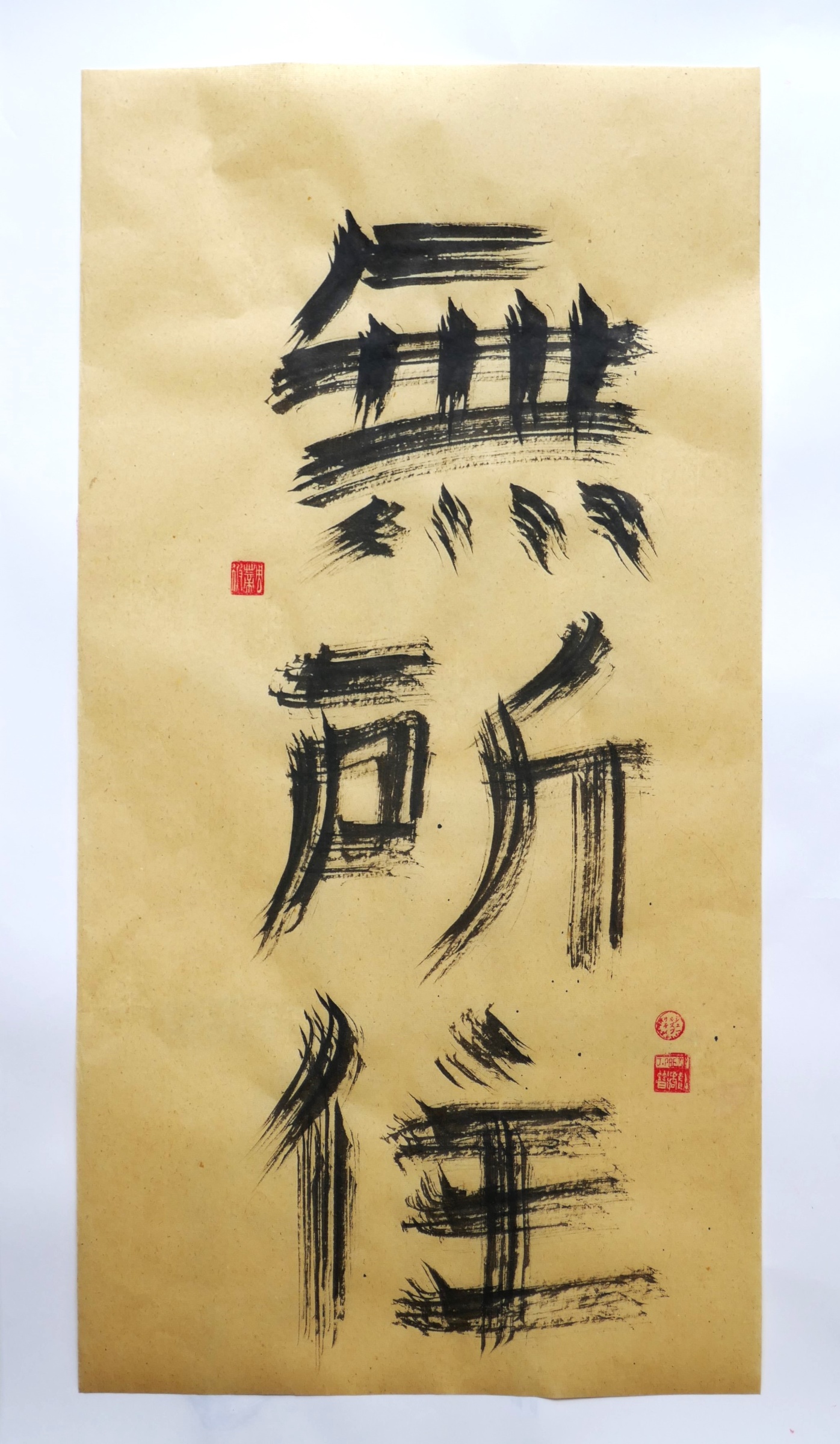

Mu Sho Jo [No Place to Live]

There was once a king’s daughter called Guðrun.

She decides to flee. Family sharks are arranging marriage.

She can fight, she can write. Now she runs and rides. She crosses the sea without a tide, comes north to a forest abbey on the isle of Sjælland.

Now she learns song and chant, and before long has become skilled in story. She soon will write a world-famed battle poem. This is nearly fifty generations ago.

At that time, across the shallow northern sea, the scribes of Jarrow are writing in their monastery of stone. They are six hundred in number, sitting daily in the scriptorium, lit by panes of glass. They are the famed poets and authors of the long-running series, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

The abbot says, “We need more field scalds and bards to gather news.”

The drafting scribe Æescferth sails to Esrum Abbey. He sees Guðrun’s verse-craft, and says to her, will you come and join our abbot’s team. So she sails again, across the wider sea.

The scribes are taking extra care under the lengthy rule of Æthelred. There is fissure at the London palace by the river. He’s trying to stay as king, to see off the Norse and Dane.

“Pay them silver,” counsels Sigeric, Archbishop of the land.

“We should fight,” says Byrhtnoð, head of all the monasteries. At the blood-stained border, pawns will lie on fen and furrow.

The abbot sends south ten scribes. Weave your threads, take a river each, watch for raiding fleets.

This is how Guðrun will soon observe the grisly death of Byrhtnoð, the famed earl of the east, and watch the sun set on any hope for peace. It is another stage in the hell-descent of Æthelred.

So Guðrun sails the sea roads south, moors by Cedd’s ancient chapel of St Peter-on-the-Wall. It is summer, the time for the second harvest of the hay on those fertile acres, fifty leagues from London’s noisy streets.

The young of Bradwell village are busy with their wedding plans. Guðrun has cased in leather a stabbing sword, a hunting bow and quiver, she checked them first for woodworm. She and fellow scribes wait, watching each and every tide.

The sun shines on St Swithin’s Day. She is patient at the shore.

One breezy morn come shouts, the children she has set as spies are running back along the village path. She saddles up her horse, rides fast toward the river mouth. A water fleet draws near, one hundred handsome sails coming on the inward tide.

And standing in the leading ship, at its crimson prow, is a man born on Orkney’s isles, his helmet bright as glass. He is pointing out the water path, they are sailing for the royal mint.

Above are skeins of charcoal geese, migrants also inward bound.

Now will be composed, a salt-marsh play ten leagues inland.

By the wetted causeway, at the foot of the hillside town, up have sailed these wanderers. Olaf’s narrowed-eyes focus on a distant court. Facing him the grey-cloaked Byrhtnoð, white-haired now, six decades a keen survivor, patron of the monks at the Ely fen.

Guðrun is now the scald, creator of the war-god wine. She’s going to tell her fellow writers of the shuddered shield and spear-dew tide.

The moon ebbs and fills, twice over. A sixæreen sails fast the many leagues back north to the River Weir. It ties up, and Guðrun limps ashore. The scribes hurry to the hall to hear her news.

Guðrun stands by the hearth, leans on her hazel stick.

She begins with sorrow.

“I can only tell you this, what I saw and what I know.”

“On a shore of saltings, at the eastern creekway, pushing up and back are bodies washed by waves.”

“These are not fishers, fouled by storm, nor fur-wrapped merchants, torn from prow. They gathered as the sky was lilac-blushed, they hear the clink of metal clasp, the scrape of leather plate. There are coughs and cleared throats, breaths pluming in the marshy air.”

“Many are thinking, how has it come to this?”

“Later, we find the earl’s body, but not his head.”

“In dead of night, we search with a minstrel’s son and a boy of the shire-reeve, for they had been sent by Ely monks. They take him north to the abbey on the isle of eels.”

“Olaf puts aground at Northey Isle, standing full in view of the town and mint of Mealdune.”

“The swifts had flown, first acorns fallen to the ground. In the orchards on the slopes are ripening pear and apple trees.”

“Water slaps at clinkered hulls, wind sighs through pines ashore. The isle has a link to the shore, the causeway dry at low tide.”

“I see Byrhtnoð walk around the flickering fires as his men eat venison, pull flesh from oily herring, splash mead from jug to cup. A single monk sits away to one side, he’s been sent by Sigeric the Bishop. Byrhtnoð walks toward the wooden door, claps Offa on his back, grips flinching Godric, wraps tall Wulfstan in a hug. He smiles at Leofsund and Dummer, young Ælfwin too.”

“Each is guessing what might be lost, as night gives way to dawn.”

“Byrhtnoð knew this shouldn’t only be a sniping skirmish. And from the moorings on the isle, Olaf calls across an offer. He’ll sail away for silver, if the money will be paid.”

“Byrhtnoð knows how to speak with kings and robbers, they will never stop the raiding. I hear him say, nor shall you carry off our riches.”

“In the evening gloom, I see a black dog walking on the marsh, its eyes flashing.”

“I warriors stroll across the wet road, staring hollow-eyed. They sit to share a horn of ale. These are family and friends, paid to face the other side. Their homes are at the deepest fjord, by handsome rivers, by plains of golden barley, near forest edge. Sharing words are men of the nearby marsh, the muddy river-hamlets, by their fields of oat and wheat and the wilder woodland-pasture.

“And yet there’s so much to share, meat crackling on the spit, mead passed by hand, warriors sitting with those they soon would fight. They are sharing hope, those on foot and those at oar.”

“But the ground was chosen for the clash. Cut from a hedge were hazel poles to ring the field. They say grim Guðr comes, with her wave sisters Hilðr and Hlǫlek, the riders of the Valkyries, they who obey commands of Oðinn, soon to slice bonds to earth while battle rages all around.”

“Well I meet in the feasting crowd, mortal women dressed as men. Skilled fighters from the English flank, Lathgertha the light-footed, her sergeant Stikla, and from Olaf’s side, Sela and Rusila with locks tucked and lances ready.”

“These women warriors offer wise advice. Stand high as falcon, watch the battle from the hill.”

“At dawn on the open mudflats, under the calls of lapwing, there is the sough of wind, hearts are thumping loud.”

“A son of carpenter, thrums fingers on his arm. His eyes are wide, absorbing every piece of English sky.”

“A woodman wonders on his baby girl, back at the green shore by the Baltic.”

“All my children over yonder hill, blinks a muscled tanner.”

“There is chainmail clinking, swords are hissing from their sheaths. The blood-red beaks of oyster-catchers are bright upon the marsh.”

“One side moves with clamour, stamping feet with raucous cries. The other breathing silent valour, fearless with resolve. First upon the bridge is Wulfmeer, in step with cooper Maccus. They link their arms with wainwright Alfere, who loudly calls, you will not have heard of us, but we will be renowned. This path is narrow, you shall never pass. They force back the Vikings, who cannot skirt the shining mud with their heavy shields and greaves.”

“It seems like ancient gods are stepping in, as arrows swerve to hit a buckle. Overhead are ravens wheeling. Then the tide rises, and soon are locked the ocean streams.”

“I see Wulfstan crawling, he tears off his mail, counts many arrow hits, some had gone through more than scratching skin. And now he strides away, as pilgrims do, paring off a staff of ash, calling out the name of the god who has protected him.”

“Bowmen bent their backs, yet many hoard their arrows. Both armies shout across the lapping water. Byrhtnoð now lets the Norsemen march ashore, yet this is no mistaken order. They want to push the raiders back against the rising tide. To trap them, to end the hopes of Olaf.”

“Yet the Norse have three thousand warriors, they take an hour to cross, stray arrows fletching into wooden shields. Byrhtnoð has requested Æthelred send the fyrd of Wessex, bring the Kentish host.”

“But his message is ignored. From above a sea eagle views the battle lines, stretched deep and far.”

“Byrhtnoð steps forward, and some men on either side lean on spears, set down their shields in stacks upon the soil.”

“A thane races out from his line, injures the earl but he is slain. White-haired Byrhtnoð grimaces, young Wulfmeer tugs out the spear. Another Viking goes against the man, then two and three and four. His war-icicle soon is wet with blood. All his men are cheering, but then he can’t grip his sword.”

“Hateful dark surrounds him, he falls with a great sigh. His armour rings on stone, Ælfnoth and Wulfmeer lie by his side.”

“We had heard Olaf is tough to face, yet he stands afar, as men step forward to their death events. Each life is now too short for them to pay their parents for their loving care.”

“A carpenter who can turn his hand to any kind of resin wood. A cooper who can fashion barrels gasps one final breath. A weaver and her fingers, should we mention her?”

“It was all a grisly song. When the chief of Hel walks on the stage, all hope for good is gone.”

Guðrun takes a breath and stops. Her tale is done.

The scribes in the monastery are silent, then all as one they break into applause.

Æscferth stands, he asks, “What about your leg?”

She stares, flat eyed. Speaks again.

“There was a break in the Essex ranks, three men with spears raced up the hill toward me.”

“You know I fought with my brothers, so I had a mail coat under my shift.”

“Then that black dog appeared, racing downhill. And shouting up the hill came Lathgertha and her crew, their crescent shields glinting. They hacked off the hand of one, the dog attacked the others.”

She pauses.

“They’d speared me against a fence.”

Æscferth adds, we have heard that Bishop Sigeric urged Æthelred to pay, and Olaf stowed ten thousand pounds of silver, sailing east to home. It is true, the scribes will later hear from the men who pulled on oars of pine. Olaf splits the northern realm, he buys the throne of Norway.

Yet the English crown on the narrow brow of Æthelred has not grown heavy. He still is king of English ground. He is skilled in court and corridor, he has no ear for Hrothgar’s warning. No care for the pitfalls of all power, how the strength of each king fades.

So if anyone speaks ill of the cloistered king, and no one hears him, well and good. Otherwise the court acts with ruthless speed. Any chance of peace is wasted, all the reserves are looted. The bells toll upon the empty treasury, and lean years lie ahead for all.

Ten years on: cruel Æthelred turns upon his people. He says the settled Danes have sprung up like weeds, as does the corncockle in golden wheat. He and Archbishop Wulfstan order a new and deadly carnage.

It happens on St Brice’s Day. The monks are preparing for the feast of all souls. Yet now come shouts, a mob is raging in the city streets. They see brands flaming, feel in their bones growl and clamour.

They hear thumping at the oaken door, a pause as the doorman shouts back.

The crowd demands that the abbot point to any migrant Dane, for the fault is clearly theirs. This is the truth, says the king’s decree.

This descent is dark. For this is genocide of family and friend. Danes are burned in church, killed in house and out in fields.

At the monastery, the scribes rush to Guðrun.

They hide her in the vaults, behind the sacks of grain. She hunches with the rats, while the mob rages on the floors above.

Until then, Guðrun’s greatest fear is centred on the poem, how to shape a story from the melee by the mint, how to bring respect to customs dating back to Bede. She has spent a whole decade composing verse on sheets of vellum.

She has to flee, carrying nothing. The abbot sends his ship, the refugees escape at dawn. They sail in friendly mist, across the sea once more to the abbey isle.

Æthelred orders fast and prayer, his prescription for misfortune. Wulfstan joins again the fray. In his Sermon of the Wolf, he now condemns the Anglo-Saxon people for their moral failure. This is not the fault of leaders, but only of the people themselves.

At the distant abbey, Guðrun tends the kitchen garden. She raises many kinds of herb and medicine. She has again a place to live.

Only the one copy of the epic script survives. The author’s name is never found.

Jules Pretty

Commentary on Mu Sho Jo: No Place to Live

Mu Sho Jo says we might find we need no place to live. We could live in pure spirit, no attachments to things or places. No clinging to incidents or thoughts.

At the same time, physical places are where our lives happen. They provide connection, identity and hope for continuity. We might still appreciate beauty, but not desire to possess it. We have one-life one-moment.

In this story, Guðrun has to escape home to avoid an enforced marriage. She flees north by boat to Sjælland, and joins Esrum monastery. She becomes a skilled storyteller, and is recruited as one of the famed roving scalds of northern Europe in the 900s CE. She joins the great operation at Jarrow, the monks and nuns who gathered news and stories for the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. One year, in 991 CE, she is stationed at the mouth of the Blackwater Estuary in modern Essex, watching for Viking and Danish raiders. She comes to observe the Battle of Mealdune (today’s Maldon), and has to fight with women warriors. She returns injured to Jarrow to tell her tale, and write the story as an epic tale. Meanwhile the realm of Æthelred is in disarray, all reserves spent. He turns on his own people, and order the killing of all those with Danish roots.

Guðrun is saved, and flees again by boat, back to Esrum.

The epic poem is found hundreds of years later, but the final pages were burned in the Cotton Library fire of 1731. It is officially recorded as anonymous. The poem has no author, so the records say.

Jules Pretty

Jules Pretty