[11 mins reading time]

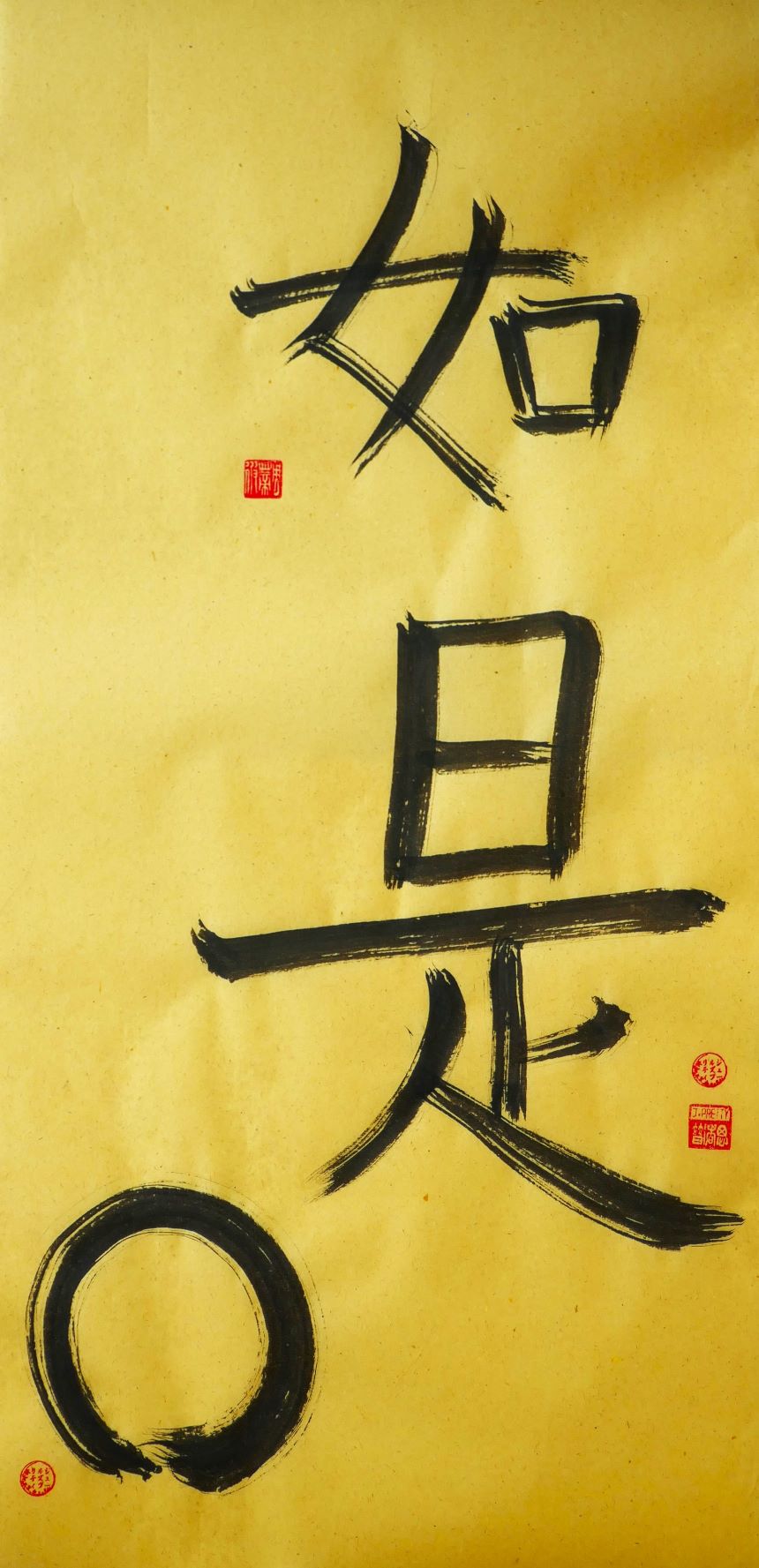

Nyo Ze: As It Is, Like This

The phone starts ringing at the remote farmhouse.

There’s already a gale rattling the windows and doors. Now the knock. Suddenly, you know everything is about to change.

It has been the worst of winters. It’s about to bring terror.

At the joy of independence, it rains all summer. Now three years later, bitter blows, more than normal for an Arctic winter.

Þórdur Jónsson has strong eyes, wide forehead, hair a little tangled on top. He has an impish grin, is as strong as the god Thor. And much more reliable. He listens to the coastguard.

He’s already thinking about a rescue mission. Inside the fjord, or outside by the cliffs? How to find the ship? Every farmer of these cold plains is a partner in the rescue squad of Latrabjarg.

An English trawler, mayday signal, somewhere on the rocks, and yes. Maybe at the base of their cliffs. Now to contact all the neighbours.

So what do these fisher-farmer communities choose to do in Iceland? They rescue others in the game.

That is how it is.

In the dark days of December, a helpless trawler is wrecked at the base of half-kilometre cliffs. The next year, in the same month, another is stranded round the corner.

These fearless farmers, they are sure-footed as sheep. From the sky above, down the rescue party drops. They have long rowed, setting hooks from sixæreens, mittens frozen stiff. Here is cold sea-current, flowing south from Arctic Sea. Here onshore winds churn waters rich in food for fish and birds.

It’s the greatest borough of the birds, in all the northern deeps.

Now this story works its way into national legend.

In the spring, the farmstead men and women, they brush clean each suit and dress. They shine shoes and carry coats. Þórdur thinks how each witness at Thingvellir, standing at the back in rain, couldn’t hear a single word.

Yet today at the banquet, the President sits beside him, gifts to Þórdur a silver handled trophy. And pins on forty-five men and women in all, polished rescue medals. And to the faint surprise of some, five honours are sent by King George to these distant fishers.

On each tablecloth are flags of Iceland and Britain standing side by side.

Wise leaders in ages past, often see how annals might depict a story, how all might feed a common pride. This first elected leader of the isle, Sveinn Björnsson, turns to Þórdur.

He says, “Your story has defined us. I’ll find the funds to make a film. Let’s get Óskar Gislason to make for us a modern saga.”

Þórdur thinks, they’re farmers. He’s the president. Yet the gap between them seems only the width of a finger.

The actors for the movie meet at Þórdur’s farm. They tread ten leagues inland, take the crew to the cliff-top. The lighthouse looks west upon a sea of scree and skerries. It’s spring and the puffins are building burrows in the grassy turf.

The heroes spread out, lie on the turf by the gorgeous pink carpets of thrift. Óskar scopes the set. He crawls, gazes below from the brim. He turns to Þórdur, this man of soil. He asks to hear again the story of this rescue that has so captured all the country. And those of distant Fleetwood too.

“We’ll get the cameras rolling. All of you can act your part.”

So Þórdur tells of the four-day rescue.

The mayday call comes from the trawler Dhoon, its one stern engine thrashing the sea. It’s losing power. December at its worst, a ship is going on those rocks. He calls the neighbours one by one.

“Fetch horses, all the ropes. Bring rockets and the rescue gear.”

Þórdur continues. “Our force is ready, yet we don’t know where the ship is. Nor if the crew can survive, as tides wash in and out. We tie tackle to the horses, call the dogs to heel, strap on boots with nails, shrug rope around our shoulders.”

“We walk across the icy moors. At last we see from this snowy peak, waves pounding at the tiny stranded Dhoon.”

None of them need to say: it’s not like the abseiling for birds and eggs in spring. When they gather razorbills from the base, kittiwake and fulmar from the shelfs, guillemot from sheerest bluffs. This is winter, three hours of grey light. Ice on all the rocks.

“We tie twine around our waists. Six men dig in their heels, the first slips over, down through all the birds, a plumb line to the dark below.”

The men and women of these ancient farms are nodding now, pointing to the route. How they carry down the breeches buoy.

Now they drop a camera bag and tripod, all the kit and batteries. At that time, the fishers below know nothing. Later some will wonder at the choice made by the owners. This ship was called at first the Armageddon.

This tiny ship the Dhoon, less than thirty rods in length, had mineswept in the war. She’d set sail from Fleetwood. A replacement skipper from Hessle Road in Hull steams to Iceland’s western waters. Do they sneak inside the fish limits, or stick to deeper grounds? Either way, as all the fleet of trawlers facing waves of forty feet, their anchor does not hold.

One growler shears away the wheelhouse, popping planks. The sea sweeps away the skipper with Fred the fairground boxer. The bosun Albert Head, a hand who learned to sail from the eastern beach village called The Grit, now marshals all the crew. Thirst is soon their fear. They break off ice to suck. They huddle in the whaleback. Togetherness saves them. Three times they watch the tide rise and fall.

Þórdur and the fellow farmers take up the tale.

“We swing down the wintry cliff, kick off from crag, ten of us arrive at the base. The others anchor ropes up here.”

“And after Unni pitches the tent, she also drops to talk to them in English.”

“At this point, we don’t know if we’ll find a single fisher still alive. We pile equipment at a cliff-foot ledge. And pause till daylight comes, hoping they’ll see us from the wreck.”

“We drag them over. Twelve sailors are waiting, soaked by the freezing sea. Their hands and feet are useless, we put cigarettes gently on each lip, break flatbread into pieces, slide mittens on their hands.”

“I can see it in their eyes,” says Unni. “We have come down from the sky, like gods.”

“I tell them to swing their arms.”

But now her news was dreadful, a frightful prospect. They don’t know there’s still a fearsome cliff to climb.

Þórdur and the men form a chair from rope, tie in the fishers one by one, each still wearing a cork lifejacket.

Árni’s a beanpole, all angles and elbows. He scrambles up to tell them at the top to pull. Seven of the crew rise slowly to the clouds. Crawl and roll on the meadow snow, stare at the cloud above.

But night draws in fast, they can only fetch the other five halfway to the ledge of Flaugarnef. Halflidi and his climbers take off their outer clothes, they try to keep the men alive. Wrap them up, wait for the distant dawn.

Now Unni says, “They were stiff with terror, carved up by guilt. They survived, their friends had drowned below.”

“We lay them in the tent. At long last the sun rose, so we made our way. The sailors stagger on the snow, we strap some onto horses to trek the winter fields. The bosun Albert has great gripping hands, yet falls six times. Into beds we tuck them, spoon hot broth to each. None had ever tasted coffee blended with the caraway-taste of brennívin.”

“One sings quietly from his bed, staring at the sky.”

“No more, no more, I’ll go to sea no more,

Sometimes I wish boys, that I were dead,

And won’t go to sea no more.”

Soon they’re gone. They sail by trawler south to Reykjavik, take a plane to Glasgow, a train to Fleetwood. A grand reception hails them home for Christmas.

Altruism saves these men. No money is exchanged, just smiles and wrinkled eyes. What builds up: reputation on one side, lives on the other. Still, there are empty coffins at the funerals.

When Óskar finishes filming, the descent and climb now in the can, he asks: “Can we return in winter, will you help us once again?”

In the faint hours of daylight, the layer-cloud is so cold it roofs the earth and sea. All the treeless slopes and fields are bleached. The farmers put on hats of fur with flaps. Pull on roll-neck jerseys and heavy coats, saddle up their horses. Take out rope and rescue gear again, shout to the dogs, wave goodbyes again to children.

Óskar has in mind the scenes he needs. In mist and snow, shots on the icy precipice.

Now comes that other unexpected knock.

In the gale force easterlies, entering watery stage from west, another antique trawler comes. It’s the Sargon once of Grimsby, its skipper on the hunt for shelter in Patreksfjorður around the northern flank of Látrabjarg.

The skipper blindly steers, hoping for the snow to cease. A boy deckie takes soundings with a seven-pound lead.

Sure enough, their anchor drags. The crew are all from Hull, the mate and bosun, engineer and trimmer, spare hand and the deckie learners. The youngest is just thirteen, the oldest born in the days when Grimsby sent its boys as slaves aboard the fleeting system.

Only six survive this night, the rest are frozen from exposure. With grinding screech, the ship is stranded at the base of Hafnarmúli.

The rock that holds the Sargon is just two hundred steps from safety. But it is dark ashore. On deck the crew launch flares, burn each mattress. And a farmer’s wife sees the flame and phones the coastguard. A lad rides fast by horse from Þórdur’s house, clatters over slatey slopes and ice to find the film set.

The crew and actors are stunned.

They draw out charts. It’s a lengthy walk. North around their tongue of land, twenty leagues to the plain of Örlygur.

The formal court in Hull will later say the conditions are appalling. The judge voices admiration for the shore party. He knows this is not the only stranding where rescuers had been so willing. Yet he sends no special message, neither thanks nor medals.

sThe Sargon has one lifeboat, a lifejacket for each man and boy. But the icy waves thrash the deck, set solid over every metal surface. Six of the crew are sheltered in the whaleback, the other ten and skipper are back inside the bridge.

The wind is ferocious.

Óskar’s camera keeps jamming. After dawn the breeches buoy is finally fixed to the hull, and a fisherman straps in. Now the farmers scamper in the waves, they pull from salt six ashen men.

None of the crew from the wheelhouse escape.

The woodbine funnel still is straight. It seems not far, from bridge to bow. Þórdur and Árni haul themselves aboard, slip on ice, grab at frozen metal.

At the bridge lies the skipper, all the windows caved in. The door is broken, they find eight other bodies squeezed together. Two are plainly boys.

They shout with joy, for here is a man alive. He flutters eyelids, but they can’t free his fingers. They’re frozen to a metal post.

He dies before their eyes.

Death has scythed the crew of Dhoon, it’s taken too this gang of Sargon fishers.

At the court in Hull, in the columns of the press, no one seems to know these are the very medalled men and women who had rescued Dhoon.

Days after the rescue, Þórdur and the local sheriff, the sea now mirror calm, motor round to the Sargon. They hope to retrieve the frozen bodies of the fishers from the bridge.

They find in horror open tins and bottles lying on the deck. A man must have been alive, below decks. But now there is no sign of life.

The waves take the ship, break it into pieces. The sea has it still. The hull of the Sargon lies there still, red rust rising as the tide ebbs daily.

The rescued men are soundless too. The mate of Sargon retires to spend his life as master of a tethered lightship. Though the film will tell the tale, the rescuers stay silent, some so traumatised by double deaths on ships.

It wasn’t just the cliff rocks that fell and struck them blows. It was the death of other men and boys, before their very eyes.

An 80-year-old famed skipper from The Grit, a childhood friend of Albert Head, later says, “You know we were more tolerant and kind in the days of fishing. When we sailed and steamed far to other ports and places. And came back with gifts and stories.”

In Hull mourners lay heavy stones inside the coffins. To give heft for bearers as they stumble from the church to grave.

The fishermen sigh a little inside. Shoulder their long bags.

They’re off to sea once more.

Jules Pretty

Jules Pretty