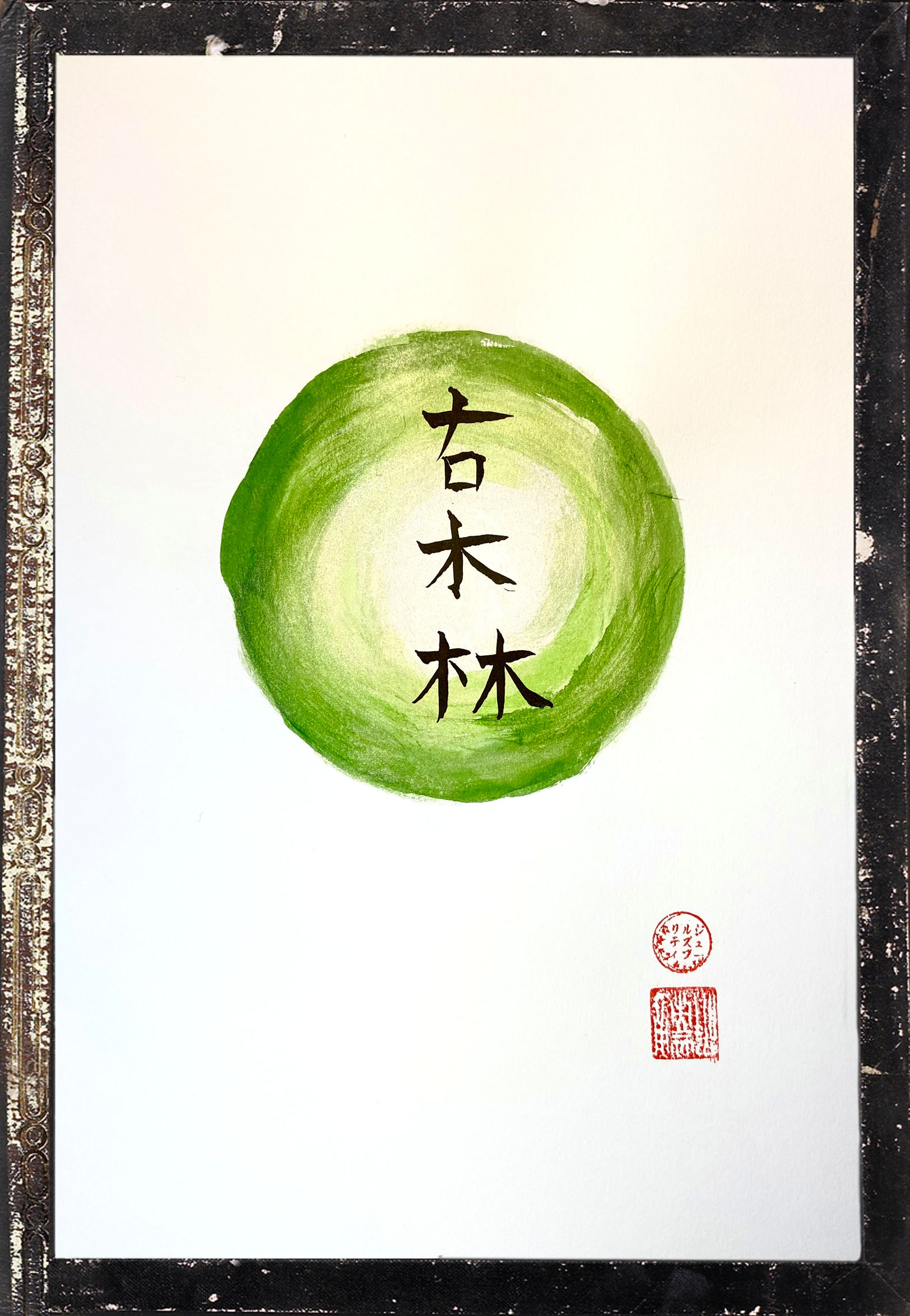

Ko Moku Rin [Ancient-Tree-Forest]

Spring bulbs are blooming, it is time for a tale.

A word then, for all the ancient standing people.

The trees older than the forest they stand in.

It may sound better if you put out the light, listen to the tale from between the sheets that hint of lavender. For though the Standing People are patient, they still do much for us.

There is an old queen of the forest. This is Erce with the rowan-berry lips. She loves to laugh. When she enchants the trees, there is hope they can avoid the axe, the crazed intent of fire and flame.

Long ago they say, an acorn falls, a single mast of beech, a paper willow seed, cypress cone and hanging fruit of baobab, they drop to each place when the world itself is young. This is before the age of city states, before the later crashing crises.

None of the Standing People are lonely, one oak one fir one pine. All are connected underground to hundreds more. They share food and water through the roots, speak in fungal tones and tenses. They talk to birds perched on their branches, to insects in their leaves.

As each tree grows, it becomes a book of branches.

After all, in the ancient tongue, the word tree means letters of the alphabet. It means learning from those all around.

Now Erce sees an acrid haze is hanging over the valley. How it tracks the river line, each bank hemmed by factory and chimney. She has watched them appear, the builders and the breakers, she has even seen single trees abandoned in a field.

Erce knows how to bring about fruitful fields and harvests, yet her influence is ebbing.

It’s the natural cycle of things. Birth, death, disappearance. How a crow scares the colour out of the land, leaves dark night at the end of things. How a bone fire creates a harsh smell that clothes the hollows of the land.

This is also the age in which it’s become common to believe you can plant an acorn in the morning, and expect to sit in shade by early afternoon.

Some say this is also when mice begin to run after cats, and lions be chased by rats. For blow after blow, sadness is filling the sky.

Erce calls on Gawain and wise Hare, the nimble runner, the peddler and tinner of the paths. She calls on Woðin, lend me your Sleek-Blue twins.

So Gawain swings up to his saddle on mare Gringlolet.

Hare and the Raven twins run and fly, first to the eastern shore. There is a row of salt-killed birch, upright driftwood all bleached and skinned. The glistening river murmurs in and out of miles of mud. Curlew call, overhead are lapwing. Light rain faintly falls.

Shuck is waiting. World trees are falling from the cliffs. He can do nothing about that. He shares his news.

Gringolet has enamelled nails on her bridle, a splendid saddle skirt, and Hare skips beside. The Ravens croak to one another, bouncing along and their feather coats loose and shimmering. They have their pathless ways.

Laughs Hare, “You’re lucky, you never normally see Ravens until the best part of the day is done.”

“Well, we often sleep slowly,” says Munnin.

In the second parish they come to a single patch of parkland, the twenty-five oaks their beseeching arms raised up. They are sculpted and few have leaves. For these oaks are there in Erce’s book of branches, they are already old a thousand years ago, woodgrain swirled and becoming every kind of pattern in the rain. These oaks where the saint Francis stood and preached to birds, to animals gathered up beneath. The trees are that old when Woðin himself is strung upon a nearby Ash.

There is always more than meets the eye, in any ancient forest.

They come upon a girl carrying a basket, her cloak and hood all scarlet. They came upon a boy, who has sold a cow for beans, he has them in his hand. They come upon a cottage in a glade, its door open to the morning air. All is quiet.

At the darkest hour, has said Erce, she who had the finest eyes of all the forest people, at today’s darkest point, there is no path. Ask the Standing People of the forest, for they will surely step aside.

In the third parish, there is an old man outside a cottage, all around the seeping chatter of sparrows. He stands with a staff, and is holding out a hand. The birds crowd for the seed, and he looks up and smiles.

“They only want the earth,” he says, waving the band on.

In the fourth parish, they come upon a young woman gathering herbs, her long hair streaming as if a day’s tempest touched only her. The clouds have blown far away, and the cold day shines brightly forth. She laughs and points them to the west.

In the fifth parish is a river crossing, over deeps where demons lurk. The cold air whispers as it passes. Wild are the storms, these days, when they come. Each can swell a river, loosen rock and break a bridge, weave a mesh that seems to edge away from hope.

Gawain knows all the back ways, the sunken lanes and people who had lived long on the land. He has ridden far on Gringolet, over rivers and hills and broad plain.

So far, it seems, so good.

Well Gawain of course is quite a knight. He is young when Arthur’s Court was old and the varnished Round Table already scarred and chipped.

Gawain is thinking of the Round Table, and how in those days they think they deserve to go on forever. And how no one knows where Arthur and all his other friends have gone.

In the ninth and tenth there are settlements of thatch and tile, warm and folded down between the hills. A village where swifts in summer scream around the spire. There are knotted eels, bubble-chains from the searching otter, old ditch lines filled by lodges and dams built by beaver men and women.

In the eleventh parish, they come upon an elderly couple. They are seated on a bench, before a fine orchard of plum and apple, a clear stream chuckling over stones. The man is called Old George and the woman is smiling and says she is Annie. She clasps a basket of dried herbs and autumn flowers on her knees. The band stops at the gate.

“Do you want high or low,” she asks.

“What ails you, what kind of magic do you wish?”

And Hare turns to the band and says, these are my oldest friends. Famed in this very parish, they roam at night, bringing hope and health.

It is unusual for there to be two healers in one family, yet here they are. Each is slim and slight, both seer and whisperer, herbalist and enchanter. George is first called Old when he’s in his twenties. They live in a flinty cottage layered with the dust of a thousand drying herbs and fruit, in the pungent air of plants.

There are some nice touches. Flowers in a butter churn, strips of bamboo for ants to walk from apple to pear branches, frog-spawn in the pond, swallows nesting in the eaves.

Annie takes from her basket rice cakes and a gooseberry pie, passes them to the band. The cakes are sweet and taste of melon, the gooseberries are from the cottage garden, baked in this magic pie.

Old George says, “This is what has been foretold: abruptly birds will grow dense, fall from blackened sky, animals will hide inside caves, bees inside their hives.”

“Praise no day until evening,” Annie adds. “No blade until tested, no ice until you cross it. It will be the greedy people who eat themselves to lifelong trouble.”

By the twelfth parish, the band has arrived at the hilltop copse of smooth-barked beech. There is a carpet of flowers on the chalky downs, orchid and red burnet buzzing with bees, self-heal and sulphured lady’s bedstraw.

They can see the whole hoop of the world.

They can see ghostway and drover road and sacred tree, each distant isle and estuary. They can hear summer, the gentle sound of the air, the flow of rising sap and sugar. The summit trees have grown up here beyond the clouds, rooted in the dry chalk, and their leaves now rustle and flicker. They are home to a great flock of crows and many a rook and chattering jackdaw.

“I helped plant these as saplings,” says Gawain. “They live here well.”

They are the tallest Standing People, these beech so close to sky. There are nine hazel trees on the eastern side of the copse, the nuts were said to hold magic and are gathered each autumn by the wise.

The beech trees can recall electric clouds level with the ground, thunderous rain hurling itself and the copse noisy with sheltering sparrows. Things grow old so quickly in the fields, rusted and ploughed and eaten by iron from above. There is no wind, and yet there comes a rushing and a rustling, as if a hundred thrushes are on the forest floor, searching in the autumn leaves. The dry beech leaves shiver and shake.

“Well, what now”, asks Gawain, looking down on far fields.

They go west toward the setting sun, for above the fiery desert are the cool forests of pinyon and juniper.

Gawain and Hare take the trail up to the oldest beings of the all the parishes. The Bristlecone Pine is weather-beaten, scoured by lightning and storm. Its trunk is corkscrewed as if the land itself has turned sharply and twisted all the ancient giants where they stand.

Each tree has few leaves, so the Ravens perch on their branches, Gawain sets his back against a warm trunk. Hare’s honey-coloured eyes are gleaming.

Well that’s enough, for they ride and run east and come to a mountain pass in the final parish. There by a Shinto shrine is the Childbirth Chestnut, ko’umi no tochi.

This ancient chestnut is tall and handsome, its broad trunk has a bole about knee-height.

Here a woman finds, nestled in a blanket in the hole, a smiling baby.

She so wanted a child, and one spring on a day like this, there the child found her.

For centuries people walk here, pick up bark shards from the ground, nuts too, grind them into tea. It is a way to ask for children, to ease a child’s birth. They hope a child will find them.

Hare puts her paw in the hole. It feels warm.

Gawain says, Bashō the poet-pilgrim wrote about this tree. He knew then about the wet world that was soon to come.

“The horse chestnut of Kiso,

Souvenirs for those people

Of this floating world.”

This is what ancient trees do. They look after the future for the people.

Great trees teach wisdom, says one of the Raven twins. Nature is always correct. It just needs an incantation to help the people.

At dusk in Erce’s forest, two stag beetles whirr, clattering into the canopy of birch. A bat slides silently in the warm air.

The World Tree has been safe, connected to every other. And in a far-off hamlet, there are happy sounds, children running in the morning mist. A broth cooking over coals, older men and women standing up to face the sun.

And when the sun rises, it lights the branches of the Standing People.

It bathes them in a glow, it warms their leaves and trunk and roots that go on drawing up the water.

Jules Pretty

Jules Pretty