[9 mins reading time]

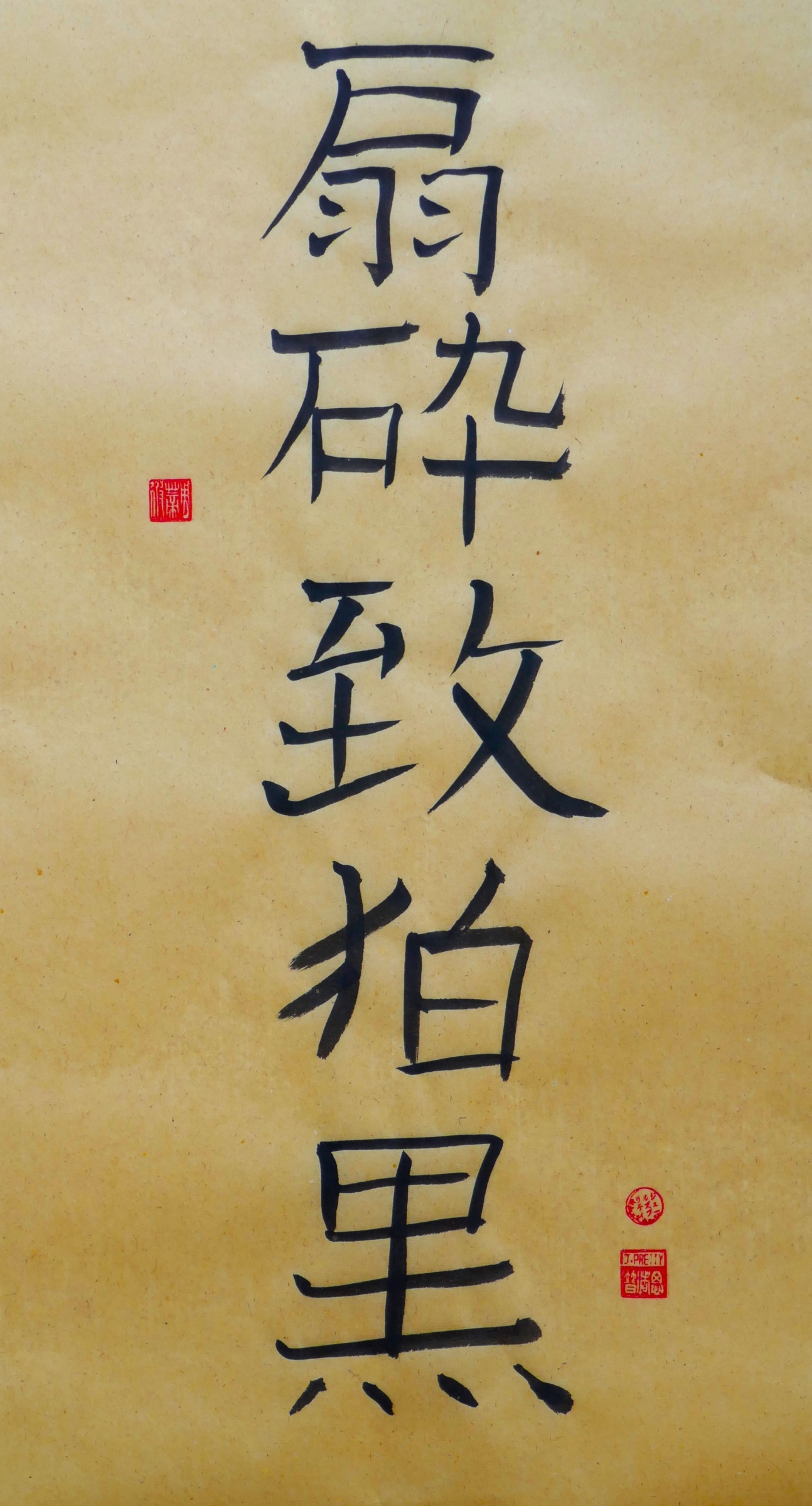

Sen Kudukeru, Chi Koku Haku [Fan-Broken-Bring-Black-Hound]

The old dog is walking along a cliff.

Prowling some might say.

He is padding quietly. Across slopes that have slumped and fallen over the years and months and days. Along paths that were previously far inland.

Once sleek, now ragged and worn, whiskers grey, eyes often bloodshot. These wardens, just out each night doing an ancient job of vigilance.

And by god, they still can run. Faster than a gale.

And yet, it doesn’t seem quite fair. Best friend of the people for all that, over all these centuries. He feels at times like a sparrow flying from one end of the longhouse to the other, from darkness to darkness.

These days people seem mired in new sort of turmoil. The dogs hardly know what to think.

Do you think it will turn out alright?

He runs into the glow of gasworks, a dirty town stained by neon light. Where gas piped along the seabed comes ashore to burn a smoky wind. One day soon, the salty tide the highest known will dash up, slap homes with once fine views, scatter cars and shatter windows, come close to breaking through.

Now it’s spring. Brighter days, plum blossom, the first sprays of blackthorn in the hedges. Daffodils in the churchyards, though the geese have not yet flown.

Oh yes. All sorts of wonders. This tale does go back a long time.

This is the coast, after all, where the woodland King Herne stood beside Queen Erce, and they looked upon a sea. Where once it had been dry. Their fine black hounds stood at the cliff top too, watching death approach.

You break a lovely fan, and imagine that. No one knows what to do. Now again the coast is being put to ruin.

Time to call upon a trusty friend?

On fresh nights like this, the descendent guardian hounds first of Woðin stalk the silent paths, from site to site of ancient bloody battle. Shuck’s seen stuff you wouldn’t believe.

He runs over fen and marsh, down green lane and up again. Along the sea cliff, to fields that slide away so fast. Over paths that led away to cliff edge and cold air. Around each crabbing boat and lobster vessel drawn up high, all their pots in piles.

He runs past cottages of pebble and flint, screens flickering in their own ghostly light. All is quiet, it is long-past closing time.

It’s been happening again.

This time to the descendants of the people of Doggerland.

Once there’d been a wide plain, many roaming herds, nomadic hunter-gatherers, birds who filled the sky. Then the ice begins to melt, quite fast. And the oceans fill and overflow.

Doggerland is drowned, and the sea’s never been quite the same.

The people, they flee of course. That’s all another story, filled with the loss of home and heart. They never knew why the sea had turned against them.

Today you may choose to sit upon a cliff and look east to the sandy sea. You may find fishers who trawl up bog-oak shards, mammoth bones, the limbs of humans. You may hear them say the bells of churches can still be heard from undersea.

It is on a night like this that Shipden church clear slid away.

The tall Sidestrand tower slipped down the steep, far from the fair green corn and fields of red poppies.

The banded Haisbro’ lighthouse has seen all the homes of Beach Road go.

You can safely swim at Dunwich cliffs, only now to 1760 or so, for the rip tide out at 1550 will haul you fast away.

On the Holderness coast, on the far side of the Wash, thirty parish names listed in the Domesday book, all have tumbled away.

One summer’s day, one hundred years and more ago, a paddle steamer belching black smoke sailed too close to Shipden church. The steeple split the hull. The crab hunters still call it Church Rock.

Shuck can shriek. Can only do so much to protect the people from themselves.

Some assume it could be a dark figure with blazing eyes. Some will say, that could be Shuck the Black Dog, the one as big as an angry calf. Some kind of devil figure intent on harm. Some say you can hear the clinking of his chains, or sometimes he’s walking without his head. Or you can feel his hot breath from the shadows.

Which is ridiculous.

They’re just dogs, not something from fiction.

It’s almost as if, he says to their friend Reynard, the kings and bishops wanted them to be devils. Rather than friends of the people.

He says, “Sometimes you can’t joke with people. They don’t seem to want to laugh.”

On nights like these, it will be Shuck and family who are out walking. The dogs with many names, Old Scarp, Skeff and Old Snarleyow and Galleytrot. The hounds of Oðinn or Woðin, depending on where you stand, commanded to be wardens of the coast. They’ve been on trips to Portland Bill to meet the Row Dog, to the Channel Isles to see the Dog of Bouley, even to Peel Castle to walk with Mouthe Doog.

But they can’t cover all the places. The coast is too big and wide.

Now Shuck pauses at a tide mill, takes wooden ways on ligger boards, stitches the web from place to place, is gone inside the gorse. You may see his lantern eyes, you may think them brake lights, odd that a distant vehicle would be high upon the cliffs.

Gulls hover in an updraught. It’s that time for boat-cleaning, crab-pot repairs, for gazing at the great rollers thumping on the land.

You may hear a howl, for Woðin’s dog will call when the coast seems about to fail. At the edge are wheat fields, clawed away and crumbled by the sea. A path leaps to outer space, old safe ways have fallen far.

And so the frothy sea below, it advances all the closer.

What of these hounds, whose footfalls make no sound, one of whom bursts into the marsh cathedral at Blythburgh, by the salty marshes?

If the dogs could speak, if those Elizabethan parishioners holding prayer books now printed in English, if they would have listened, then events might have been more orderly.

Still, they mostly do survive. It is the year a great comet appears in the daytime sky, when Drake embarks to sail around the world.

A summer’s evening. All is mayhem. Thunder and lightning flash. Humid air inside.

The south door bursts open, under the priest’s stone room. Firelit shadows rise and race, leaping and pulling back. Candles gutter, some flare brightly in the sudden wind. If only the dog could speak.

Or that the standing people now would listen.

So beneath the wooden angels high on spans of the nave and chancel roof, the hound howls and runs down the aisle, from font to pulpit.

The dog runs past the carved poppyheads and golden robins on the wardens’ staffs, he roars and runs up and back. Stands right where today is a crucifix carved by a Southwold fisherman from a piece of Dogger oak dredged from the sea.

The parish people run too, spiralling outward to the north and south walls. And now a rumble starts in all their bones. The steeple falls. It crashes through the roof, pieces landing on the empty benches.

One man and his son are later found in the wreckage.

Shuck claws at the locked northern door, forces the oaken timbers open. The survivors dash to safety in the rain.

The hound’s nightwork is done. He slips away to check the tide, along the old river walls.

The people change their tune. This horror must have been the work of demons. Left on the door, the claw marks are a warning.

This is the land after all, of a phantom drummer, green children found in a woodland pit, the wild merman of the shingle shore, shrieking pits at cliff-top church. This is the coast where fire appears in the water. The summer sea at Cromer, all green phosphorescence, balls of St Elmo’s fire on ship’s masts and church spires.

Some say, shoot him, lock him up. One day, Shuck saves a blind boy on a bridge at Thetford, stops him like a father. Leans in and pushes him over to his sister. Hand-in-hand, the two walk safely home, the boy chattering happily to the dog.

On dark nights, it is a long way down. To scramble over sticky clay, wade through seeps where springs rush down.

In that case, being off balance could bring some hope, when the coast has been so shattered, so bring us our old companion hound. Bring the dew, the smile of the newborn babe. A chancel boy who sings, a girl who rows the ferry boat.

Could Shuck mend this broken fan, could he transform fear with hope?

It’s going to take some bright kings to do this.

Meanwhile, summer advances. The trees are in full leaf.

On the bare cliff at flinty Beeston Regis church, by the ancient priory where monks still can be heard singing to the sea, the moon rises from the ocean at the winter solstice, a glittering path to the far horizon.

Each summer solstice, on the old Queen Erce’s birthday at dusk, they return to gaze upon their windows from the churchyard. A robin is singing from a gravestone.

The pets in the static caravans, hemmed between church and cliff top, they bark and yip, and a woman mutters, shush what’s got into you tonight? A man is whistling, looking out to sea.

The dogs never did hear what happened to Herne and Erce. Shuck fears it might simply have been that people forgot about the old gods.

The year’s been the busiest ever. The job’s imposing, longer hours, more people to warn away.

“Certainly not,” says Shuck. “Tomorrow’s another day. And the views along the coast can be gorgeous at this time of summer.”

Shuck and his family, his faithful wife and their four sons and daughters, they look up. For there in the centre of two stained glass windows are their portraits.

All six of them. Looking towards the sea.

Rolling their eyes.

Jules Pretty

Commentary on Sen Kudukeru, Chi Koku Haku: Fan-Broken-Bring-Black-Hound

This koan has been working on people for thirteen hundred years. In the original, it was a rhinoceros fan (made from horn). Yanguan called to his assistant, bring me my fan. It’s broken he was told. In that case, he replied, bring me the rhinoceros.

Now his assistant was off-balance, spinning away from the perfectly ordinary day. Most of life is inconceivable, the idea of bringing the Black Hound may also be unimaginable. This was the black dog with blazing eyes who roams the coasts of the East, the one who broke down church doors and brought fear. Yet maybe we could bring something different to this tale.

In this case, how about the boy who sings in the desert, a girl from a sacred mountain, the dew on the grass, the mist before an autumn moon, the smile of a new-born baby. If you feel broken, if you have a thing that is broken, the coast or the sea perhaps, then take it outside and see how it looks and feels. Being off-balance could lead to hope.

After all, Black Shuck broke down the door of Blythburgh church to make people flee to the side walls, just as the steeple crashed through the roof to the aisles below. All were saved.

If the climate is broken, what could we bring?

Jules Pretty

Jules Pretty