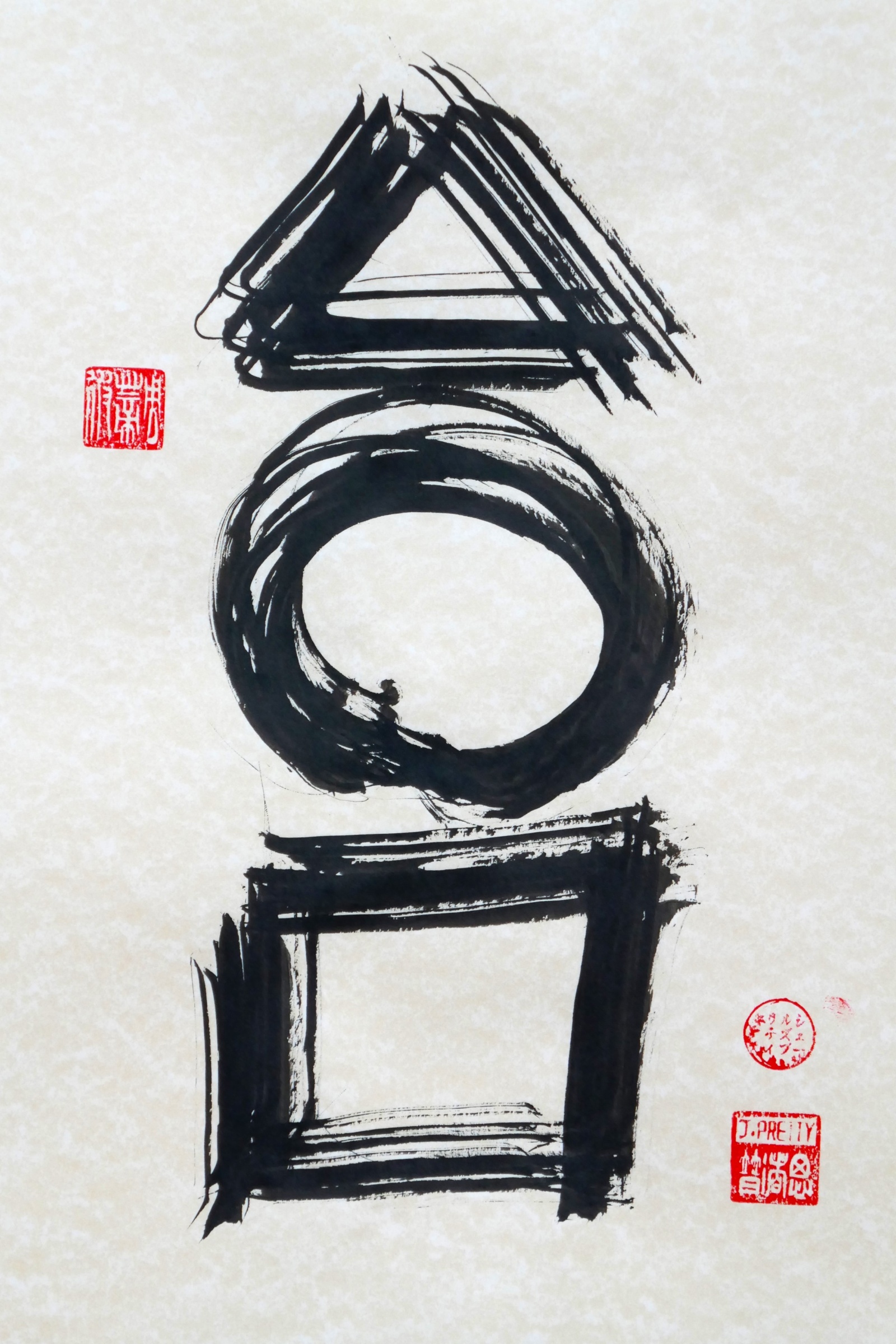

[Ensō: People, Spirit, Earth]

Mid-Atlantic. It’s the isle of the bird people.

Taught to climb from childhood, growing up stocky and agile. Ankles doubly-thick and toes elongated. The flighty people who climb the crags, collecting birds and eggs.

Looking out from the St Kilda group of isles and needle stacs, the tallest at six hundred feet, they see only ocean. Leagues beyond leagues, then yet more sea.

The main isle’s called Hirta, the Gaelic term for Earth itself.

There are on a planet, and all around is space.

It is a sea bird station, great numbers of fulmar, gannet, puffin. Shearwaters that had in previous times blackened the surface of the sea. The birds, mostly at sea in winter, then flighting in as the days lengthen in March and April.

The people see before them, the first fresh food since autumn.

Right there in the river of the ocean, the Gulf Stream that flows round them. From west to east and warms the higher latitudes of Europe. Clear and clean, many fish. A hundred miles from any other land.

Fires in homes burn all year, it is so for two thousand years. Perhaps more. No one would ever let a fire go out.

It’s wet.

A place of rain, a metre and a half each year.

The missionary’s daughter, Mary Cameron, says, “One storm left us deaf for a week. Wind, pounding sea, thunder and lightning, windows white with spray, wind coming through the walls, sheep blown off cliffs, all the land a rushing river.”

The waves crash right over the five-hundred-foot anvil summit of Dùn and crash on the stone houses of the village.

A visitor writes: “The people of St Kilda live a very happy life, better housed and better fed than most others on the mainland.”

In 1930, all are forced to leave.

Someone decides, progress calls.

These distant islanders are to enter the wage economy. They speak only Gaelic. The costs of evacuation will come from their future wages.

It’s an overcast day in late August. Raw mist rolling in from the Atlantic. The previous week has been glorious sun, now back to cold and damp, and the winter ahead looking worse.

The twenty-five homes for nearly two hundred people are abandoned. The school, the church, the circular cleits of stone for drying peats and rope and food, deserted. Left in their homes: beds, chairs, chests. Pots, pans, all the fowling gear. Hundreds of sheep transported, but many more scatter away. They hide on tiny ledge and grassy slope, far from reach.

The son of the postmaster says, “We were running away and leaving everything.”

A stone is tied around the neck of each sheepdog. They are thrown off the jetty.

Weeks later the post ship returns. It finds the bay still full of dead dogs.

Some of the evacuees are allocated jobs in the Forestry Commission.

“What use was that?” says an island man. “I’d never seen a tree in my life.”

In 2005, a plaque is installed on a rock at the pier. “Welcome to St Kilda, natural and cultural World Heritage Site.”

St Kilda is out beyond the sunset isles, out from the ship canal dug by Vikings from shore to safe inland lake at Rubha an Dùnain. Far from the slopes of Skye scattered with sheep and wet crofter ruins, out through the Sound of Harris where currents clash, far beyond the setting sun.

For half a day the boat slaps down on incoming ocean swell, the grumbles from an air storm gone days before. The white spray thumps high, it breaches the cloud low and grey.

In days gone by, this journey takes an open longboat sixteen hours, rowed by stout men of Skye.

A gannet follows, a fulmar sweeps around the bow wave and is gone. There are Risso’s dolphins rising from the clear waters, scarred by ocean squid. There are whales, a minke with her calf, the slow arch and fall again of sleek water beasts.

Beneath the cloud appears at first a dark blur and already the lee swell is behaving. The boat motors for northerly Boreray and the stacs, rounds the points and skerries, circles back to Village Bay.

The black isles rise sheer from the ocean, far above are grassy slopes and brown-wooled sheep looking down.

This day, all is calm.

There are puffin rafts, damping down the waters, gannets darkening skies. There are northern fulmar and guillemot. Out of nowhere swoop skuas, killers they say, for the sake of it. One two three, mob a single bird, crushing it down on the rising-falling ocean swell. There is call and cry, squabble and high silent circling around the cliffs. Common seals are hauled up on rock ledges inside a seaward-cave. Gannets turn great circles in the air, searching for shadows in the water. Fish lit by light from deep below. The birds fold wings and arrow, one after another, the air vibrating as they slice the sea.

On these very cliffs and teeth of rock, the cragsmen climb and abseil, on thirty fathoms of horsehair rope, thirty fulmar could weigh all of ninety pounds. They eat eggs as if they are potatoes, in winter salted birds.

The way ashore was on a rib, a manifest to keep rats on boats and away from a million and more eggs and young birds.

Ahead is the ruined village, the curve of Main Street on the contour round the shore. From manse and church to the thousand storage cleits. These huts of St Kilda, built of white stone and turf, huge flat slabs for lintel and ceiling on which sits grass to draw up moisture by translocation.

In this drenched land, the inside of a cleit is always dry as bone.

And ahead too, in the middle of such heritage, the military base, the new buildings of wood and roofed by turf. In the Fourteen War, a U-boat draws up and the captain instructs through a megaphone, take cover, and seventy shells destroy the wireless station, killing a sheep. A four-inch gun rusts ashore, installed on the very day of Armistice.

And there onshore, flitting to a nest deep in a cleit wall, is a St Kilda wren, heavy with strong bill, a unique subspecies for a cut-off land.

There are burrows of the field mouse who leapt ashore from Viking longships, now twice as large as those on the mainland, large ears and long tail.

In the boulder fields, in the stone walls, petrels nest.

The Soay sheep are moulting wool, they too have evolved. They are shrinking after nine decades of better survival for smaller lambs, sheltering in the dry warmth of the cleits.

A single painted lady butterfly crosses the meadow.

This is also unique: the St Kildans of this isle have their own ensemble way of living. Each morning, they meet to decide on tasks and a fair work allocation. All have an equal vote regardless of croft size and status, and this comes to be called the St Kildan Parliament.

On the other hand, one man writes, sometimes everyone talks as loud as they can, all at the same time.

After egg and bird gathering, then the sharing by the parliament. The larger the family, the bigger the share. There was no payment by results.

In the oval cemetery, above the black houses on Main Street, each roof tied down by warps, are banks of iris. Writers of the later middle ages record song and poetry, dance and summer games on the beach.

It has been true, too, that the religious life of St Kilda became strict, brought from the mainland and isles in the early nineteenth century. The church is austere, no altar, no decoration, no fixed pews. To the right of the room is the door to the schoolroom, also under tall ceiling and windows. The children clamour in winter to come to the front of class to read aloud, for then they can stand before the fire.

Each day the children climb the hill to cut and carry peats, the job before the school bell.

Now all is grief.

The men weep for their dogs.

Fiona Gillies is ten as they leave, and she sees the mothers crying too, turning to one another, pointing at the cold chimneys, thinking of the peaty fires around which people sat at night and told stories of their blue-green isle, out here in dark ocean space.

There are no press photographers on the day of departure, no newsreel cameras.

The bird people are going. It is an exodus. What an earth now, they are thinking?

The last post boat clears the Bay.

Outsiders like to call this place stern and lonely. Somehow atmospheric.

A national newspaper heads this story of progress in bold: “Islanders leave their home without tears.”

Morag MacDonald says: “There is no place as attractive to me than my native land. There was community spirit, everyone helped each other. There was no squabbling.”

“Life used to be just lovely.”

Jules Pretty

Commentary on Ensō: People, Spirit, Earth

The near-circular character is called Enso. It is all the world, the planet itself, and it does not quite join up, nor is it perfect. It also represents mind or spirit, and links we people to the earth itself.

The story is set on an isle called Hirta, which means Earth in Gaelic. For the people who lived for thousands of years on St Kilda, it was a planet in the middle of space, out in the wilds of the North Atlantic.

Yet there came a time when authorities from a distant planet thought it better to have the people abandon their home, and be settled on the mainland. It was true, they could go for months with no supplies, when giant waves passed right over the island hills. Yet this was also a form of enforced clearance.

Now St Kilda has become a World Heritage Site, and home to a million seabirds, including the largest surviving colony of puffin. Rafts of puffin can blacken the surface of the pristine sea.

St Kilda had its own daily parliament, unique sub-species of wren and mouse. They kept eternal fires burning in their stone house grates.

Jules Pretty

Jules Pretty