Wild Man Running

[6 mins reading time]

Even a small wolverine can do precisely that.

Yes it might. It can indeed happen that way.

The hunter is resting on spruce boughs, woven on the snow inside the square tent. Beside lie two grandchildren, the older boys too. They are in the country to rehearse the old skills.

They have just been told the story of a trickster.

How Kue-kuat-sheu the wolverine is a wanderer. The tale sprawls, beside the glowing stove.

There is a hunter, strong and somewhat over-proud. He has a bright skidoo, a sharp eye, a fine rifle.

He is roaming on a snow road like this, through the boreal forest. The white way rolls over hill, dips down, rises up again. He is watchful, for a wolverine in the trees polishes any hunter’s reputation.

So when Kue-kuat-sheu appears ahead, the hunter guns the engine. He leans forward and now the skidoo races fast along the icy road.

He comes to the top of the first rise, the wolverine is waiting on the second.

He drives at speed, flinging snow to this side and that, and dashes to the top of the second rise. The wolverine is waiting on the third.

You can imagine, the hunter has cast off patience. And so drives faster, flies up the next slope.

And the wolverine leaps. She thumps into his chest.

The machine flips sideways, it roars on alone and buries in a bank of snow.

All is silent, even the North Wind has paused.

The wolverine stands to one side, staring at him. The gun is lying there, in easy reach. The wolverine leans forward, eyes still fixed upon him. She does not speak, she turns and slowly walks into the trees.

Yes, says the hunter in the tent, it could have happened like that.

When a hunter kills a caribou, a porcupine or any another animal, it is because the animal spirit chooses to catch the bullet. That, he says, is a great power of the land.

That calm night, the stove cooling, the tent inside glowing in the moonlight, the Innu hunter speaks again.

“Come,” he says.

“Come outside.”

So they lace on boots and snow-gear. And once again, things grow sharp and strong. The hunter sees deep down, he doesn’t need to know what’s going to happen. He presumes little, watches and listens.

The distant hills are dark. All the snow is sparkling under the moon.

The wild man called Katshi-mait-she-shu comes at midnight.

They stand beside the broken skidoo, its body parts scattered round about, the moon is sailing over an empty sky. There is a rush from far, deep inside the taiga trees. A dashing sound, the hurried phantom frame.

He sounds like he’s laughing. This broken piece of common memory. Hoots as would a hunting owl, he is behind them, then in front, this figure of the forest.

It is almost as if they should not be afraid.

The two men try to stand tall-tall. Breathing quietly, until silence comes again.

After the wild man departs, running at the speed of a moonbeam, they search the snow, and can find next morning no tracks of feet, even their own have been erased.

For the shaman-trickster never leaves footprints on the sand or snow, they fly across the land.

Back in the village, a man shouts from his doorstep:

“What are you doing here, who the hell are you!”

Inside his wooden house, water is bone and the air cold as porcelain. There is a single table, a broken window open to the wind. Ash trays are full, beer bottles strewn upon the floor.

There are curling family photos lonely on the mantlepiece.

The man has a chest freezer. Inside is a single frozen goose, its neck splashed with red.

He begins to wave his arms. And shout again.

Far to the west from here, wide-eyed wealth is stripping tar sands down to rock. There are trucks that weigh four hundred tonnes when empty. That one place is crossed by three hundred thousand pipelines, where they like to call the forest overburden. Further to the north and west a clever corporation is about to install units to refreeze the permafrost. So the drilling rigs can be safely stable.

Here the band steps out upon the frozen snow, walks to start the path to the gateless gate. The way into their ancient home.

The morning begins this way, the skidoo pieces are left for the spring thaw. The stores and food, tent and stove and furs, all packed on sleds, the runners rubbed with wax. They too will venture to the land of the lord of northern gales. They will see birds without names.

“We welcome you all,” calls the hunter.

The shoveller and mallard and types of coot, never before have they come to the homeland where people could be bears, where caribou could be people. Where huts are roofed with tusks, and tears will freeze upon your face.

This is what happens in these old days, the hunter says the next night. A boy dreams a caribou girl wants to marry him.

So he tells his father who can-not, dares-not tell him what this means.

That morning the boy dresses, ties on snowshoes. The sun is up as they reach a small hill. In the far trees by the shore is a herd of caribou.

The boy walks on alone, and one caribou stands up. She comes towards him.

He has his bow ready, his hands are shaking. His arrow heads are made from the shin bones of people.

The caribou calls to the boy, “Uh uh don’t shoot me.”

She walks up to him, and says, “Will you marry me?”

“How could I,” he says. “I will freeze to death. You eat moss, you don’t drink water.”

She says, “You won’t be cold or thirsty,”

“How could I,” he says again. “You’ll run so fast the wolves will catch me.”

The boy is nervous. Yet now he sees something sidelong. He sees a girl dressed in fine snowshoes and moccasins.

And he falls in love with her.

Together they run in a windy way, often sideways with the herd. The boy marries the caribou girl.

Some hunters have seen this boy. He runs so smoothly, people who see him say, look at the boy and his wife the caribou woman, they always run together.

The hunter says this is how we go well, with the creatures on the way.

This is how it is, a vast stillness, a silent presence stretching the land. The wind has ceased, the ice shimmers. It seems bells ring inside the cold, the moon floats in a blue-black sky, the distant mountains lit by an inner glow.

At the darkest hour, cold descends into dreams of caribou.

It is said the running people, all who live in cold climes, keep warm by kindness.

Oh hello.

It seems we’re on this way together.

Jules Pretty

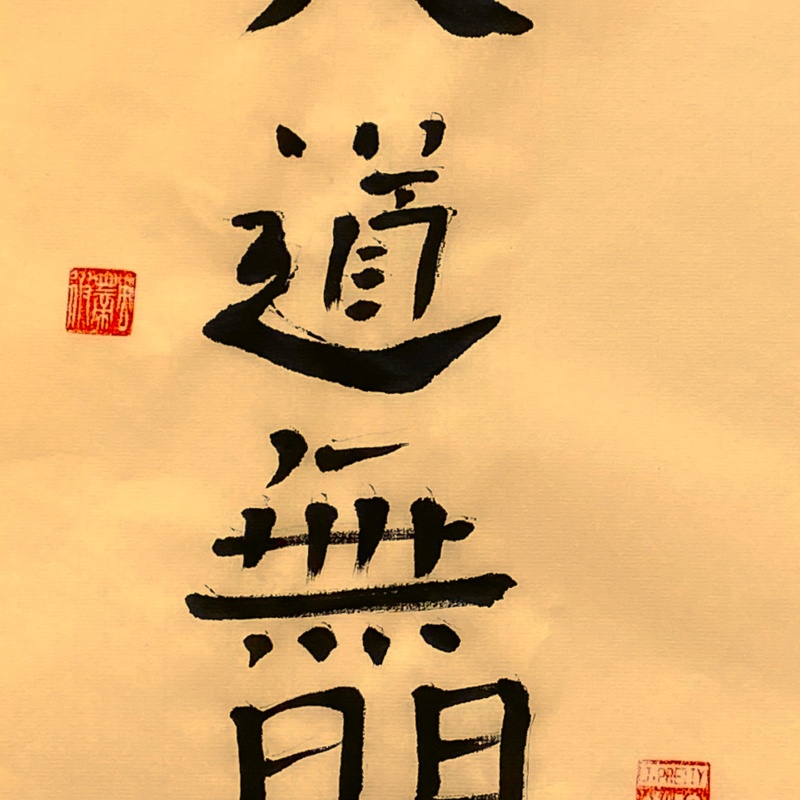

[Dai Dō Mu Mon: Great Way No Gate]

Commentary on Dai Dō Mu Mon: Great-Way-No-Gate

In the oldest surviving human stories, cave paintings in Sulawesi and petroglyphs in Australia, some human figures appear as therianthropes. They are part-human, part-animal. You sprinkle water on your face, and sprout antlers. Maybe we were wearing masks, maybe people and animals were much closer than we today believe. There was a time, after all, when people and animals could speak to each other.

The Gateless Gate and the Great Path or Way, Dai Dō, suggests there are many gates, many paths, many obstacles. There is truth in every direction, and many paths not at all blocked by locked gates we only think there may be no passage, and that old habits will remain hard to break.

In this tale, we encounter the trickster wolverine, the wild man or woman of the barrens of central Labrador, the boy who became a caribou to marry the caribou girl. It is said these running people, they were kept warm by kindness.

A lonely desperate man in the settlement shouted at me: “Who the hell are you?!”

Jules Pretty

Jules Pretty