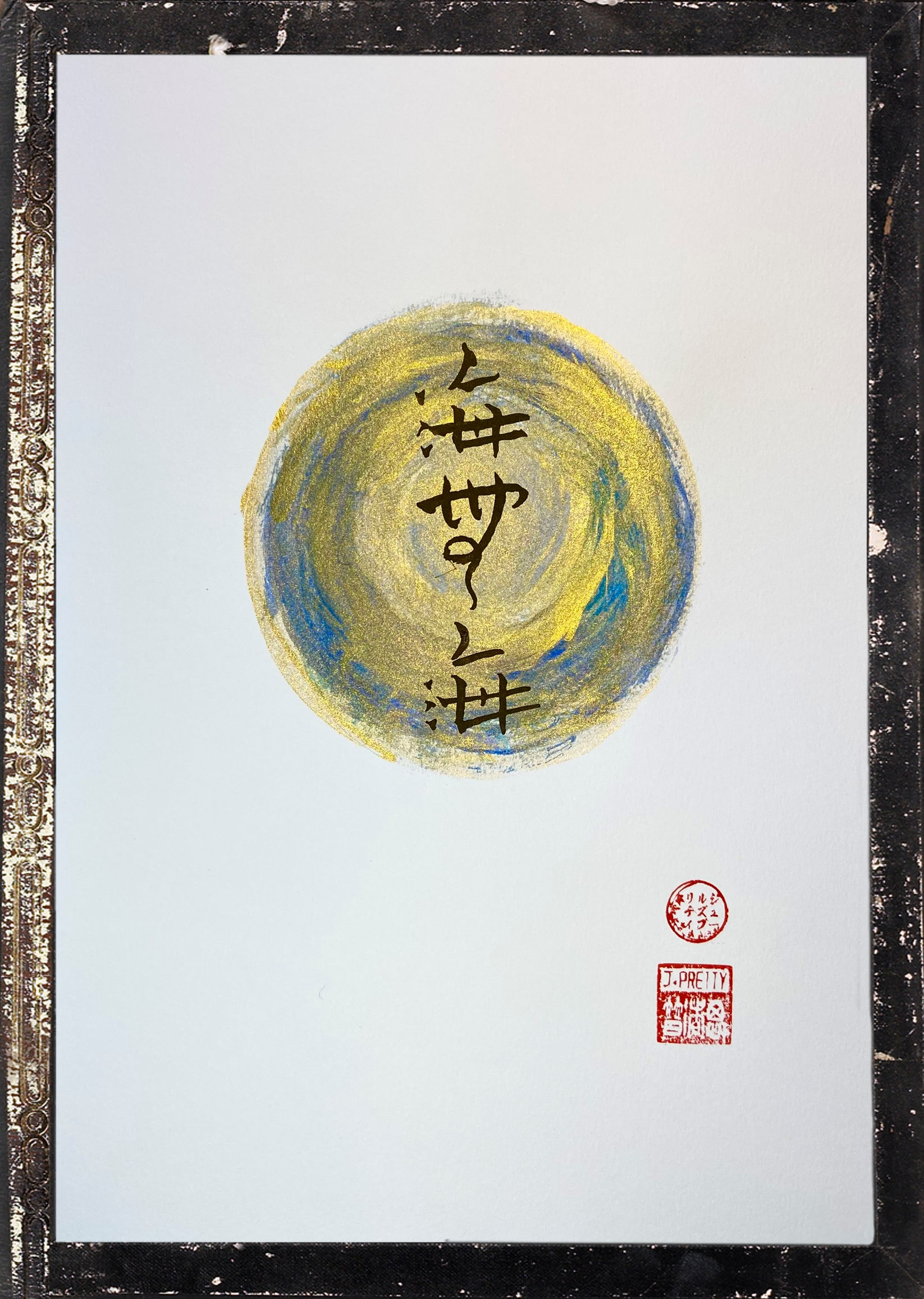

Koan: Kai Mu Kai [Sea-Not-Sea]

Sky-Ryder leads the escape.

She is tall and one-eyed, a stalker and a chaser. A fast runner of the hunting hills and grassy steppe.

It is said the Sky People once were numerous, but they were drowned. Every dark hide of land and fire pit, each vale and fell was seized by the rising flood. The swell of sea beat down defence.

This is the sea, yet not the normal sea.

In those ancient days, the good sea gods, Ægir and Ran, old Poseidon himself, they are sullen and somewhat hostile.

After the glaciers and surface ice, now water and waves. Homes and places loved, now taken.

And at the end, long years after, everyone clean forgot there had ever been a wide dry plain where now the tides did flow.

It seems no spell they cast would work. No cry to gods by these blue-eyed people, who could beat the wind and slip with bow inside the range of creatures on the hunt. It seems they cannot counter how a poison has been cast, their land that fell before the ceaseless tide.

So this. They launch their boats, lash and load the auroch-skin, flex the oars. Among the furs and flutes are sobbing infants, fastened tight to strakes of birch.

At last ahead appears a strip of land, they see a hall upon the cliff.

The brine now bears them on, toward a beach where figures stand in shadows under sighing pines. The squadron now draws near.

These are the Forest People. They’re watching the ragged fleet approach.

They draw ash bows, for this has been a year of shore attacks and sorrow, so take the strain. Herne the Hunter calls his men to arms, “Aweigh the anchors, sail around the flanks.”

But the Red Queen of the Woods, her name is Erce of the earth, she is renowned. Her long sight is best by far in the tribe.

She now calls, “I see no shields. There are babies in those boats.”

“Come Herne. We should help these people come ashore.”

After countless battles, Herne the fabled hunter soon can also see these folk are people fleeing demons. A tall woman steps ashore from the leading vessel. Others stagger at the land.

Hands pull the boats through breakers.

An infant falls. Erce shouts to the rescue party: “Watch those children.”

One is face down in the wash. A woman sweeps her up.

The boat people scatter over sand and dunes. They gaze up at mottled sky, mutter thanks to gods of solid land. They drink from skins of water that the forest people proffer.

And the dark-skinned woman, her one eye crimped, stands tall before her people, bows to the king and queen. She thanks them for their kindness.

She says softly, “We have come far, our homes have drowned.”

And the queen motions, “Lay your goods here. On the polished floor. You are safe to rest with us.”

This is how the flooded people came to tell their story. Their race from home, how their soul birds fast flew ahead.

Sky-Ryder stands with a staff that fits so well her grip. A shield of four-fold hide is slung upon her back. Above them larks are singing.

Herne calls to his servants, “Fetch more logs, stoke the blaze.”

And turns towards her people: “Come forward.”

Sky sees the black hunting dogs are wagging tails, they are running through the crowd. She sees the sea has calmed.

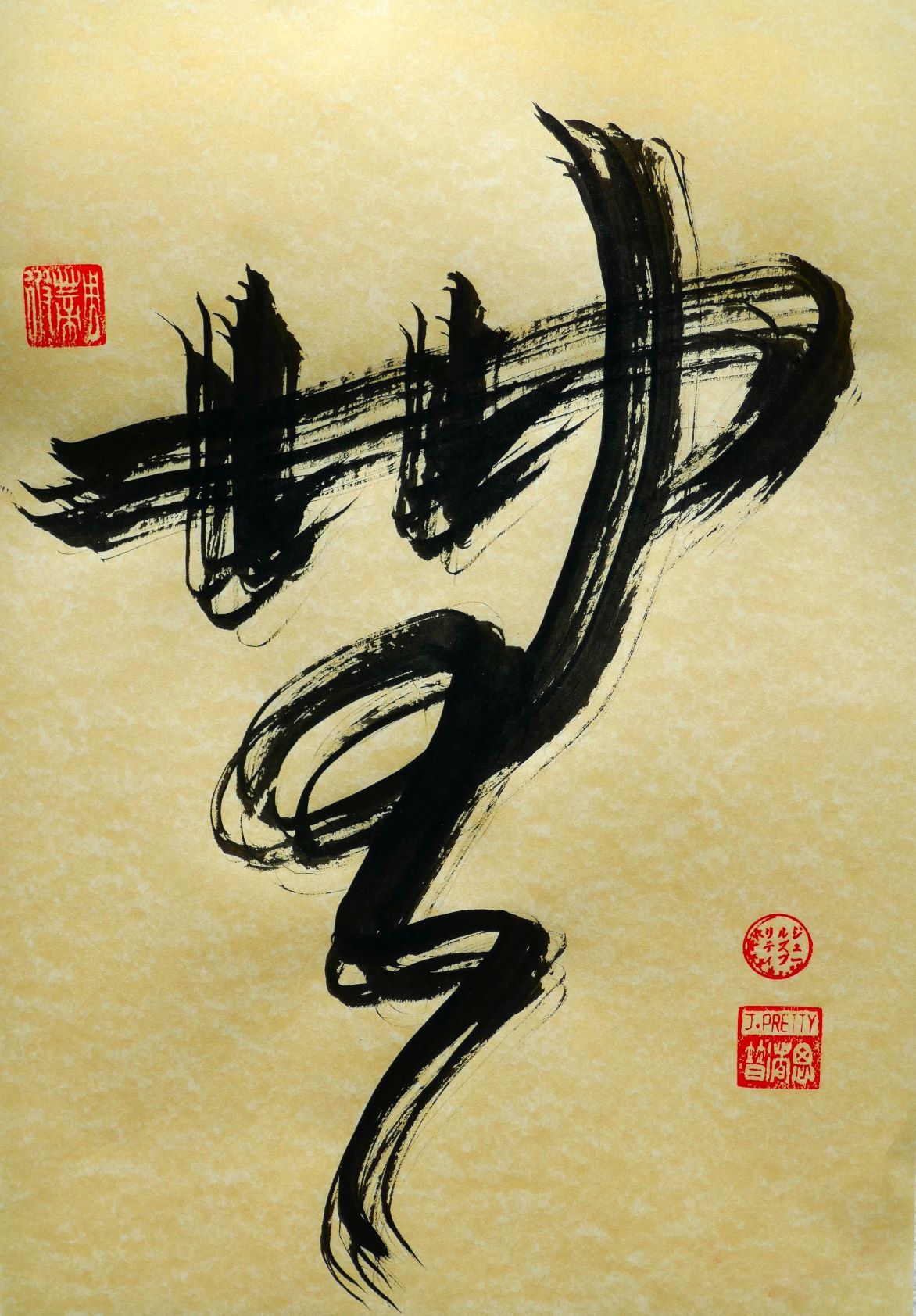

Her tale commences.

“In those distant days, Dogger was a wide dry plain.”

“On hunting hill and grassy plain, we the Sky People of Doggerland camped at salty-marsh and wide lagoon, by a million whistling waders. At the still point, a lovely ash propped up the sky, and a serpent circled all the brine, the guard of all our ground.”

“We are stalkers, chasers of the horse, the hackneys and their mares, the broad-browed aurochs and great bison herds. We harry with our hounds the giant elk and reindeer. All seemed well.”

“One day we saw a creeping shift. Those waves we begged to wait brought a great betrayal.”

“For the seas were rising up, we sensed a warp of salt and sand.”

“Each place to us was protected by a spirit guard. Each spring and cave a link between the inner and the outer worlds. We paused to pay respects and place an offering, where lancing from a cloud, light rays shone on grass so lush. It might rain for days, the dry gulch flooded. In a drought, we called on clouds and stamped the rain-dance song, till there came the glow of dawn. Our tents of skins were warm.”

“Now waves were rising, the height of you or me in half a hundred years, so in and up we carried camps. Our elders warbled lovely lullabies, watched the rising waves, the currents lapping at our gates.”

“I was a little taller than my mother, I sang before our yurts. We had to hurry, dig up a hundred holy graves, bury bones once more, lay bows of ash beside the red-deer skull, set antler harpoon by the axe.”

“I called on Woðin, desist and stop the sea.”

“Still the surge poured in, league on league not letting up.”

“We were not so alarmed, just now shifted often. We Sky People had always trekked, but routes grew shorter. Our world was shrinking, so we stirred ochre with the water from a sacred spring. And in a holy cave high upon a scarp, each tribal member held one palm upon the rock. We blew a fine red dust.”

“We wanted this place to have the spirit of an evening summer cloud.”

“The air was life to us, the wealth of sun and rain. Yet as the gannets screamed, a final storm was coming to our home.”

“Gulls seethed about the shore, sooty petrel plunged, cold-cried the cormorant, we knew it was another sign. We could not tame this tempest, all our shamans tried.”

“And one sharp dawn came a shocking sight. The sun-star rose from water, at dusk it slipped into the western waves.”

The plain and steppe of Doggerland, it has sunk before their very eyes. Doggerland is bank and swale, where once the horse had run.

Silence follows. Her tale is done.

Gripped by this spell of words, the forest people applaud, tapping the hilts of knives on hollow blocks of wood.

She has filled their sinews with every kind of sorrow.

At last Herne stretches his tendons and says, “True wealth is not the gold abandoned in our graves, in the ground. It is our sons and daughters. It is the land secure and safe beneath our feet.”

He declares a plan. “We will take you to the hills where the land is the colour of clouds, to meadows blooming to far horizons. You can mark each place, mend the moon and heal the land.”

Perhaps one day, they all will sleep without a troubling dream.

He sighs. “Light the fire pits, bring food and vintage mead.”

But then he stops and says, “So why did the sea rise like that. Will it ever stop?”

A hound barks.

From the rest of the camp is silence.

Not a fly buzzing. There’s a blue flash, a kingfisher flies towards the sea.

A cuckoo calls three times, and settles on a nearby branch.

Jules Pretty

Commentary on Kai Mu Kai – Sea Not Sea

Jules Pretty

Jules Pretty